All Japanese learn English at school – it’s the one and only foreign language that everyone must study as part of compulsory education in Japan.

And yet, you’ll find quite a number of people are still a little uncomfortable using the English they do speak – this was also not always the case mind you, in more ancient times Japanese did not seem to have major issues learning Dutch, English, German or even French for instance), and this state of affairs is definitely changing with younger generations and Internet-led globalisation.

Comfortable or not, English is quite present in Japan, thriving in three major strains:

First, there’s boring old Standard English, (英語 eigo) which is what it is, along with two much more colourful local forms: wasei eigo and kazari eigo.

Wasei eigo

Wasei eigo (和製英語 literally made-in-Japan English) consists of English words, or idioms, which are either pure Japanese creations, or actual existing English words that were given a Japanese meaning or usage quite different to what is found elsewhere.

These are extremely common in Japanese (dating back to the post Meiji-Restoration “opening” of Japan of 1868), and an integral part of the Japanese language.

Some classic example of wasei eigo would be the 1920’s mo-ga (モガ) from modern-girl, bakku-mirā (バックミラー) for a car’s rearview mirror, or kanningu (カンニング) an adaptation of the cunning, which is not an adjective in Japanese but a noun meaning cheating, especially in an academic context (more examples of wasei-eigo can be found here).

Kazari eigo

The other major form is kazari eigo, (飾り英語 literally “decorative English”, sometime nicknamed Engrish, Ingrish or similar) and this is where things start getting amusing…

Kazari eigo is basically nonsensical, or just plain weird English words or phrases, used as decorations on Japanese products intended primarily for the Japanese market.

It’s fascinating – at first at least – to imagine someone sitting down and dreaming up these oddities, and presenting them to who ever is in charge, and the whole thing being validated.

It’s one of those things which, along with Takarazuka Revue posters flashing at you in the morning train, either makes you love being in Japan or want to go back to bed, depending on your mood of the day…

To cherry-pick an example given below, someone, somewhere, at some point in time actually sat down and drafted the following:

“We are the GroupConsist from the from Person Who can stand on One’sown Always Be able to Help Eachother That’s The Spirit of RESCUE,MANHOOD/

The produced by >> SAS Corporation”

Pretty high-octane stuff, right?

Sure, every one can have ups and down, and maybe extreme overwork, feverish delirium or hallucinogenic substances like underground shōchū moonshine were involved at some point in the creative process, who knows.

And yet, this Dadaistic copywriting was also validated somehow (at SAS corporation, in this case, confident enough to even sign off as The produced), and ended printed on dive-equipment roller bags meant to carry innocent divers’ gear around the world…

We don’t really know the brand’s actual history, other than SAS’ Japanese history began in 1976, as the local branch of some US equipement maker…

But this is beyond the point. Which is is that somehow, through some mind-boggling process, English words and sentences that do not make any sense, or if they do, are either ludicrous or sometime even downright shocking, ended up printed on products sold in stores across the country, and sometimes beyond…

One does wonder why the company, like so many others, never had a native speaker of English check the darn sentence, either formally (by actually paying someone qualified to do so and avoid international exposure to such ridicule), or maybe informally, le’ts say ring up an old’ English-speaking buddy and run the latest batch by them to see if there were any red flags, dinner’s on me next time, yeah?

But no.

And how could this be, one might naively ask…

Well, the reason is actually quite plain and simple.

Other than the odd pair of non-Japanese eyes who should be minding their own business anyway, no one, and we mean no one, actually cares about this.

As the name implies, English here is used for decoration, not actual communication, no one reads it, nor is intended to read it and, even if they did, well, cry your heart out if you want but no one gives two hoots. There.

It’s often less the case with products intended for the international market mind you, and there’s a good chance the trend will dwindle out over the years, as the younger generation not only speaks better English but is a little more aware of these little issues.

But in the meantime, it’s still going on strong.

Example abound, here for instance, or here, here or here.

And let’s not forget the French equivalent (kazari furansugo), which has its own niche in classy products, the Franponais.

Other kazari uses of languages exist, we’ve seen a few examples of decorative German (kazari doitsugo), and no doubts other variants exist.

Speaking of which, is decorative use of a living language really one of these only-in-Japan things?

Broadly speaking, yes, but decorative Japanese (kazari nihongo) does exist, though it is much less common.

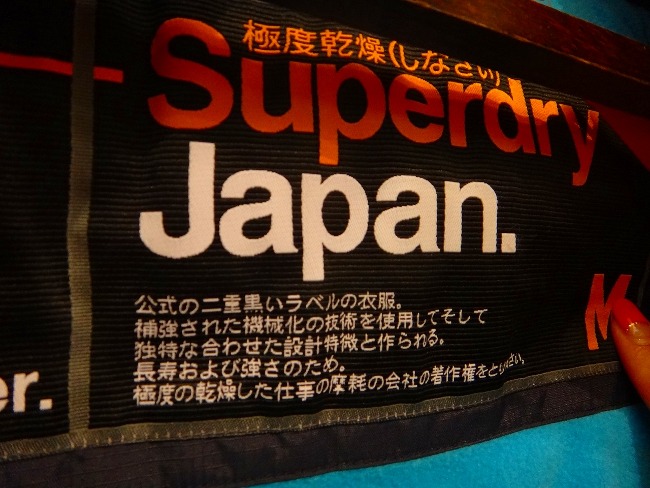

Beyond the famous odd or mistaken use of Chinese characters in tattoos, the title of absolute master of decorative Japanese equivalent is proudly upheld by a clothing brand: Superdry.

The undisputed king of Kazari nihongo

Superdry’s decorative Japanese does have Japanese speakers chuckling away discreetly, which is understandable since the brand’s most commonly encountered slogan『Superdry極度乾燥(しなさい)』is a heavyweight combination of a Google-Translate nonsensical translation of the words Super Dry with, in brackets, an injunction to “please do”.

And the clothing brand certainly does not shy away from broadly communicating in a non-proof-read, no holds-barred decorative Japanese.

Could this actually be part of someone’s revenge plan for all the infamies of kazari-eigo in Japan?

Who knows…

Wasei eigo and kazari eigo in the diving world

When it comes to diving, most Japanese terminology is either wasei eigo type adaptation of English terminology, mostly correct, but with expectable oddities.

A surface-marker buoy is called a float (フロート ), and a shore entry, whatever the terrain, is always a beach-entry (ビーチエントリー), because, well… life’s a beach?

One of our favourites has to be the slightly slangish term daikon (ダイコン) which refers to the white winter radish in standard Japanese but, in the diving world, is a stylish contraction of dive computer (daibu-konpyūta).

Other examples can be found in our diving Vocabulary section.

As for kazari-eigo on dive gear and association products, yes we can goto!

Two main brands Japanese equipment brands, Bism and SAS dominate the Engrish market, offering high-level kazari-eigo which, given the fact that enthusiastic divers often travel the world to dive, is surely bound to bring a few smiles on a dive boat…

Here’s a little selection, enjoy it while it lasts!

Image sources: Gull Kinugawa, Bism, SAS, BreakerOut

The produced by >> Blue Japan