Culture

Japan's Guided Diving

JAPANESE DIVE GUIDES

Image source: WTP Official Blog

Local ambassadors and naturalists

Japanese dive guides are quite remarkable.

Not so much for their diving or safety skills (which mostly follow RSTC standards and, as always, depend on the abilities of their own teachers and personal experience) but certainly for the type service they strive to offer, and also for the local naturalist knowledge they are required to possess, in order to meet the expectations of the most demanding divers they might guide.

It is quite common for guides to do part of their professional training where they will be working, as a form of internship.

This is also quite common elsewhere around the globe, yet the expectations are a little different in a Japanese context, meaning that the training often includes a great wealth of knowledge on the local environment, marine life species and general ecosystem.

Japanese diving does not have the division commonly found worldwide, where diving instructors somehow outrank dive guides in the diving industry (or, as is commonly found in South-East Asia, instructors are foreigners with language skills and dive guides are experienced local, with more or less formal training).

Almost all guides are instructors themselves, but who focus on guiding rather than teaching.

And there is a lot of respect for veteran (= highly experienced) dive guides in Japan, specialists of the local area, and for dive shops who have been around for long enough to become a local authority (such operation are called shinise 老舗 in Japanese, which is an important concept extending way beyond the diving world).

Similarly, dive staff will be quite proud to be employed by such well-established and recognised dive centres, which is a form of recognition, and also to work under / learn from famous guides.

This does not mean that all Japanese dive guides are highly trained marine-biology specialists, but it is indeed generally the case that they possess more extensive knowledge about local species than most of their non-Japanese counterparts.

It just comes with the territory, and the general expectations of divers themselves, linked to Japanese diving culture’s specific interests in endemic species and local forms of marine life, including variations of otherwise common reef fish for instance, that would normally not attract much attention. Japanese guides are usually quite knowledgeable about juveniles, marine life cycles and behavioural patterns.

Japanese dive guides are usually expected to offer a good tour of local highlights, actively spotting marine life for the divers (often less inclined to try to find stuff on their own) and, importantly, to not only lead the dive but also ID marine life in real time and engage in active, entertaining underwater communication by writing on a slate, and also often to lead comprehensive log-book sessions.

It’s a dual-sided relationship, which usually works quite well, as many Japanese divers and photographers are enthusiastic about fish ID’ing, especially when it comes unusual, rare species or really tiny critters.

Some divers are deep into fish ID, sometimes bordering obsessional (there is a word for that in Japanese, komakai, meaning small, but also picky and meticulous) – which means that guides and operators catering to such advanced guests really have to be at the top of their game.

On the other end, the dive professional’s passion for diving also blends quite smoothly with a sense of local pride, that you’ll frequently encounter in Japan.

People are proud of their local specificities, whether natural or man-made, and keen to share them with visitors.

In this sense, Japanese dive centres and guides act as ambassadors of the environment they operate in, and will do their best to help visiting divers experience its uniqueness, often with a heart-warming passion and dedication rarely found elsewhere.

This is one of the truly great aspects of so-called Japanese-style diving, a personal investment, from the dive centre’s boss (who is often the operation’s most experienced, top guide) to younger guides, a real dedication to the local sea’s wonders and delights, and a desire to share them with visiting divers.

Photography specialists

Another important aspect is photography.

The vast majority of cameras today, including the world-leading brands such as Canon, Nikon or Panasonic, are still produced by Japanese makers.

And while the world has evolved since the clichés of the 1970-1980s camera-slinging Japanese tourists always snapping away, needless to say, photography is big in Japan, which is definitely still one of the world’s photography hotspot, and this goes for both topside and underwater images…

Japan is also well placed on the underwater light and strobe market, with brands like Inon or RGBlue.

Interestingly enough, while the cameras used around the world are mostly Japanese, Japan hasn’t seen the rise of leading domestic brand of underwater camera housing. With the exception of Sea&Sea products, the most commonly encountered housings being, as elsewhere, those of Hong-Kong-based maker Nauticam).

We do wonder if this is not insurance related somehow, with a reluctance from potential Japanese makers to take responsability for unavoidable floodings with expensive cameras.

Image source: www.hirasawa-mc.com/fundiving

Japan offers great wide-angle and macro photography options, and many Japanese divers dive with cameras, ranging from to compacts or the ubiquitous Olympus TG series, to micro 4/3rds and DSLRs.

A very large part of Japanese diving-related publications is dedicated to underwater photography, there is a larger market of very enthusiastic amateur photographers diving with pro-grade equipment.

And when it comes to underwater photography, macro life is really excellent, as is the number of rare, colourful and endemic species found in Japanese waters, which has no doubt contributed to the specialisation of dive guide and operators, especially in areas with smaller marine life and generally calm conditions, such as the Izu Peninsula.

Some Japanese dive guides are true photo specialists – either photographers themselves guiding photographers according to their specific interests while providing technical tips in informal master-classes/photo-safaris, or simply guides that are very experienced with working with photographers, and able to not only find the best subjects, but also help with timing and other photographer requirements such as ambient light and water conditions, positioning or behavioural tips for shooting specific animals.

The level of service offered in this regard is quite unique, and rarely found outside specialist macro destinations such as Lembeh or Anilao.

Charisma-guides

There is a tendency for experienced guides, especially those who have been around for a long time or pioneered a diving area to be highly regarded and sought-after as the best representatives of the environment.

Japanese society is quite hierarchical, and its culture is one that loves rankings, (which is nothing new, Edo-period visitor guidebooks ranked local highlights such as soba noodle shops, kabuki actors and even courtesans of the capital…).

Dive guides considered the most experienced in their local domain, actively involved in promoting are sometimes referred to as “charisma-guides”, in other words, charismatic figures of the dive guide world.

Image source: divenavi.com www.facebook.com/divenavi/

And this is quite unique.

It’s not so much that there are no examples of such charismatic dive guides in non-Japanese contexts – dive-guide legends such as Larry Smith immediately come to mind, but also explorer-guides have pioneered diving in new areas such as Burt Jones and Maurine Shimlock or Edi Frommewiler and others, or researchers specialised in certain marine life (such as sharks, whales or manta rays…), who offer cruises dedicated to certain encounters, for instance.

And yet there’s something a little different about the Japanese concept, which is a strong sense of localism, and good-natured pride.

Guides are publicly recognised as the best ambassadors of the region they represent, and divers will actively seek these local specialists.

Another interesting aspect in Japan is the existence of an actual Japanese dive guides’ association, the Guide-Kai or Japanese Scuba Diving Guide Association which groups dive guides, including many of Japan’s charismatic and respected guides.

Image source: guide-kai.com/

Another curiosity is the existence of actual rankings.

Japan’s biggest and oldest diving publication, Marine Diving, along with Diver magazine are actively involved in this.

For instance, in this article Marine Diving asks active dive guides to recommend… other dive guides.

The article also specifies each guide’s “lineage” or filiation, i.e. who they worked for in the past…

More importanlty, Marine Diving issues yearly rankings and awards for the most popular diving areas, operators, both domestic and abroad, but also for slightly more suprising categories such as :

most popular dive guides in Japan

most popular Japanese dive guides working abroad

most popular diving instructors

which is probably not something found anywhere else…

Image source: Marine Diving 2021 Awards

UNDERWATER SLATE USE

Image source: Diver Online

Underwater writing slates are nothing new.

Slates and other means of written communication have been around since the beginning of scuba diving, as an alternative means of underwater communication in our so-called “world of silence”.

The main underwater communication method remains basic and conventional diving hand-signals, taught in all diver training programs regardless of federations (descend, ascend, stop, etc.).

These basic signals can also be extended for specific underwater communication purposes, such as more complex dive profiles, training contexts or fish ID.

The main alternative to hand signals is underwater slate use, which is not uncommon worldwide.

Most dive professionals do carry some sort of slate, as writing is an easy and rather fool-proof way to convey more complex information efficiently underwater.

Diving instructors will often have agency-provided training slates, serving as memory backups and to keep track of progress, and make up their own slates for courses.

Guides and even fun-divers will usually have a small slate tucked inside a pocket somewhere, just in case something happens that calls for clear and rapid communication of complex and unplanned for ideas.

And technical divers rely on slates and other means written communication as a complement to other types of advanced signalling and as personal memos – having clear, visual check-lists, dive plans, run-times, gas switches is a basic requirement, and tech divers often use multiple page wrist-slates during their complex dives.

Technical diving does also makes use of a precise, extended range of signals (including touch codes, such as coded taps or tugs, a little reminiscent of the surface-to-diver line tugs of the hard-hat divers of yore in low-visibility and/or confined environments)

And yet some for of written medium is always included, which makes sense, given the level of exposure, conditions and complexity of the dives undertaken.

Commercial diving, on the other hand, has gone the fully verbal way since divers mostly use full-face masks, which can be equipped with communication devices, and also require communication with the surface, meaning slates are rarely used, or only as emergency backups.

Something else

We’ve been diving with a small pencil “emergency” slate pretty much since our first days as certified scuba divers, and while we’ve only rarely had to use our slates while guiding (non-Japanese divers, that it), we now always bring magnetic slate while teaching.

Indeed, magnetic slates are great for entry-level teaching situations as they allow you to communicate smoothly with a student during training, without needing to surface, especially useful to explain what they should focus when working on a skill.

In a training situation, being able to talk underwater is sometimes precious.

Image source: www.sea-point.co.jp/

However, beyond this rather specific usage, you make sure to remember that real-world diving situations your soon-to-be-certified students will encounter will rely primarily on hand-signal based communication, hence the need for the student, from entry-level diver to a divemaster trainee, to develop clear and efficient basic underwater communication.

Which means to be fully proficient in basic hand signals and to use them effectively.

Congratulations on your AOW cert ! – Image source: www.akasyachi.com

The general idea is that, outside technical dives (where slates are mostly personal memos), slates are not to be relied on, notably for safety response reasons.

In the traditional sense, slates are primarily a back-up, or an extension of hand signals, when these are somehow insufficient or inadequate to convey information on the issue at hands.

However, this is not the case in Japanese guided diving, where slate use has evolved into something quite different.

Japanese diving has developed a unique parallel culture of underwater slate use, where the dive-guide is expected to actively communicate, in writing, with the divers she or he is guiding

Many Japanese divers also carry a personal slate, but for the dive guide, it has now become something of set requirement, an expected service, reflecting a specific approach to guiding.

And the very nature and form this underwater written communication takes is also quite different from what non-Japanese dive guides would use a slate for.

Hand signals are written on the underwater slate for practice.

Image source: PADI Japan’s Discover Scuba Diving program booklet

As a practical illustration of how much slate use has permeated Japanese diving culture, PADI Japan’s brochure for the PADI Discover Scuba Diving program introduces basic hand-signal practice… using an underwater slate!

The instructor is to pratice underwater hand signals with the DSD participant using an underwater slate…

Interestingly enough, a Japanese language version of the PADI program’s standard brochure already exists and, as a simple translation, does not feature this extra element.

However, this is PADI Japan’s own brochure, intended for domestic use, exclusively on the Japanese market, hence the slate…

The big slate

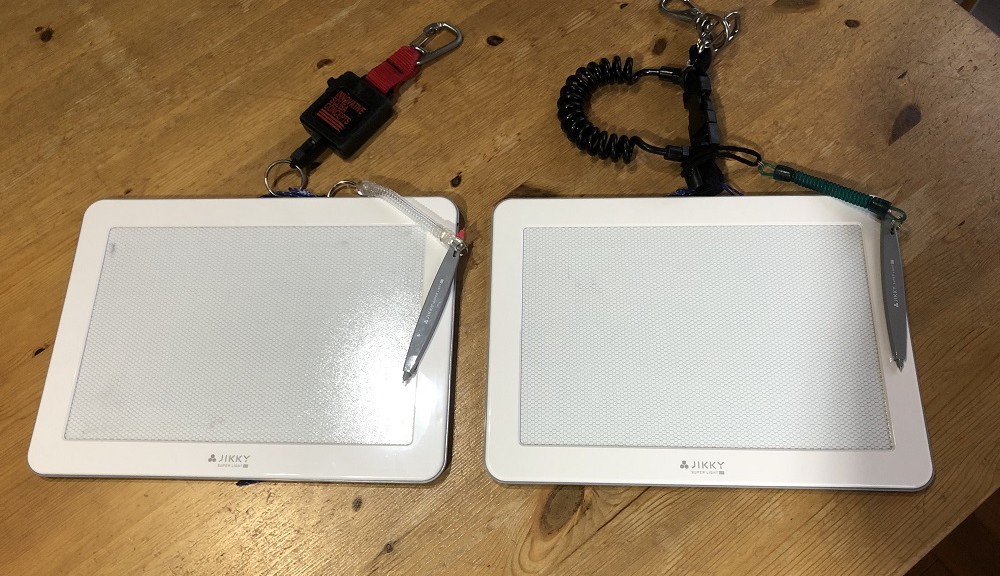

While underwater slates commonly used around the world still often consists of some sort of plastic coating, on which you write with a pencil, Japan has turned to magnetic slates for ease of use underwater, since they can be erased in one swipe, allowing for more fluid communication.

The slates guide use are general quite large, since the guide will be showing his writings to all of the divers, and letters needs to write big – some guides might use smaller slates in current or rougher diving conditions, but the most commonly used slates are large plastic contraptions, designed for use by pre-school and primary school children on land.

Image source: sotoasobi.net

Big slates do affect your way of diving and guiding, and can a bit of a handful in strong current…

As a side-note, at one dive centre we worked at on the Andaman Sea, non-Japanese staff gave the big Japanese slate the affectionate nickname of surf-boards.

Giant-stride entries generally mean holding the slate vertically over your head, and most guides would write their name in big bold letters before jumping, and hold it over their head once on the surface to signal their guests that where they should be heading to regroup….

Until recently, one of the most commonly used model was a large magnetic slate called Sensei (by the toy-brand Toby), very sturdy and with an easily recognisable design.

Most of the Japanese guides around us used this model or a variation, simply removing the stars and heart design magnets and adding some sort of carabineer or clip to secure it to their BCD.

Recently however, smaller magnetic slate models, either specifically designed for underwater use such as the very widespred Innovative Scuba Concepts Quest Underwater Slate or diverted from land use (such as the slimmer, and more stylish Jikky slates) are also gaining in popularity.

Why are slates so important, and what do Japanese guides use them for?

As a basic rule, Japanese guides are generally expected to communicate actively – and politely if possible – in writing with the divers they guide during the dive.

As guides, we’ve worked in Japanese and non-Japanese environments and have had to carry and use the slate in a Japanese style..

By slate, I mean the big magnetic slate, rather than the small emergency/back-up pencil slate we both carry in our BCDs.

Having extensive guiding experience in a non-Japanese context, and having been in charge of guiding Japanese guests in contexts where no one forced us to carry such a slate – and not having had a real problem with it – we did (and still do…) question the purpose of big slate use.

The first reasons given to us by our Japanese seniors were safety, which we never found truly convincing since:

a. we did already carry an emergency slate in a BC pocket, which we had rarely had to use in the thousand uneventful/eventful dives we’d guided…

b. it didn’t seem very realistic to try to handle most underwater emergency situations by trying writing things down.

It became clear that when it comes to slate use, the main reason is service.

An underwater service

The active use of slates by dive guides has developed, in the relative isolation provided by the Japanese islands and the Japanese language, into what could now be called a cultural tradition of its own, and slate use generally perceived as offering guided divers a superior form of customer service.

Image source: marineartcenter.blog.fc2.com

While all divers do learn fundamental diving hand signals during training, their use in a guided situation is now slightly less common in Japan than elsewhere.

Since Japanese dive guides, instructors and often divers themselves are now expected to carry slates when diving, written communication is clearly becoming the norm.

Naturally, this doesn’t help reinforce sign communication and its use, which is now becoming more basic in Japan than elsewhere (and Japanese diving does tend to use slightly different signs as well, as explained here).

Whenever possible, Japanese guides will mostly communicate through writing on the slate during the dive, and are now actually expected to do so, as standard customer service.

This means that in most situations where non-Japanese guides would use diving’s universal hand signals to lead the dive, Japanese guides will rather write things down, including phrases covering basic dive leading indications.

It is not rare to see a guide write indications that would normally be conveyed by a couple of hands signals, such as “Let’s end the dive now, and go to the safety stop”.

The phrase is written on the slate, and shown to all the divers in the group – more polite, surely.

Yes, this is a generalisation – it does not mean that all Japanese guides always do this – it would not realistic to attempt this in drift diving conditions for instance, or when a quick reaction is called for – but guides using slate-based written communication is indeed becoming the norm in Japanese diving, whenever conditions allow it.

The use of complete sentences can be quite surprising at first.

It’s important to understand that the guide’s underwater magnetic slate is not for jotting blunt, basic commands, but rather full polite sentences.

And beyond dive leading indications, there’s all the rest.

Having a slate underwater opens up a whole world of underwater possibilities…

Small jokes, comments, even anecdotes, and everything a guide is now able to tell guests underwater but couldn’t without a slate (which does beg the question, should you?)…

Over the years, we’ve seen pretty amazing things written on our Japanese colleagues’ slates, ranging from “ this fish looks delicious!” , “the current is a little tiring, don’t you think?” , along with riddles, advice on camera angles and much more….

Some guides will even draw underwater!

Thanks to the magnetic slate, Japanese dive guides can communicate politely, share knowledge directly underwater (!) rather than have to wait to have surfaced, and generally entertain guests underwater.

This type underwater customer service is becoming part of the job, along with safety and orientation.

This can sometimes be a bit much, with dive guides re-orientating a school of fish towards guests for instance, or being quite tactile with marine life…

Other aspects of dive guide service can sometimes include over-the-top diver management and “assistance” (handling certified diver’s air consumption for them, taking off guest’s fins for them in the water, etc…).

As a side note, unlike some Asian country, swimming education is a compulsory subject in Japanese schools (which all have access to pools) since roughly 1961, so swimming is normally not an issue.

However, certain guests, regardless of age, do seem to lack the mimimum physical fitness and endurance to be fully autonomous in a diving context, which can add to dive-guide responsabilities, even for non-openly disabled divers.

Image source: oceana.ne.jp

Fish ID

The other main purpose of the big slate is Japanese-style fish ID.

And slates are great for that, especially for advanced divers and photographers.

It’s not only in Japan, by the way.

Indonesian friends of ours guiding in Lembeh would usually carry slates, and would write both the common and Latin scientific name of the rare critters they had spotted while the photographer was shooting away, for reference.

Another Lembeh operation, the Lembeh Resort, explains it on this page :

“the guys at critters@Lembeh Resort all carry slates & actually use them to communicate! Strange concept I know.

aving been to various countries around the world, I’ve seen plenty of divers agreeing to have seen something when its clear they haven’t. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard “Well I saw something, but didn’t know what you were looking at” – So, slates in hand, the guides here are well prepared for pointing out critters, even to those of us who have the occasional bout of brain fog “

But macro critters or not, systematic underwater slate use is becoming the norm the land of the rising sun.

In Japan, scientific names are rarely given; it’s usually just the common Japanese name (which, by convention, is always written in katakana script).

But the name is rarely given as such.

First of all, it’s usually given in a full sentence, if conditions allow, think: “If you look over there you can see a thorny seahorse”).

And then there’s usually some kind of extra information, ranging from info on the fish itself and its ecology, to comments like “ I’ve never seen so many here!” , “the current is getting a little tiring, isn’t it…“ It’s super cute” or even “ Manta poop. (Pink) ” –

This last example is one of the first things we saw on a guide’s slate sitting on a staircase since the day before – which does make you smile on a sleepy morning at 6 am, especially when you know that specific slate belongs to your charisma-guide of a boss…).

“Manta poop (pink)“

The big slate is all about communication. In Japan, this underwater communication takes place at different level from what is encountered and expected in guided diving elsewhere in the world.

It has also become a necessity for guiding, because Japanese divers do not learn fish ID signs.

While fish ID signs are not really standardised, and certainly do have clear limitations, they are quite handy for basic fish ID’ing purposes, but in Japan they are almost never used nowadays – and why should they, since guides have magnetic slates – in fact, we’ve often heard guides snigger at the confusing similarities between hand signals for a triggerfish and ghost pipefish, for instance…

And yet we believe that the issue at play here is not so much the efficiency of one system over the other, but rather a question of what is expected of a dive guide.

Unfortunately, non-Japanese-speaking guests will rarely get to experience the big slate use as just described, unless diving in a mixed Japanese/non-Japanese group led by a Japanese guide.

Indeed, slate use implies reading Japanese, some knowledge of common Japanese fish names and, interestingly enough, most Japanese guides seem to be happy to do away with the bg slate whenever they’re not guiding Japanese divers…

We’re convinced that the decision to favour slate use, and the extended verbal underwater communication they allow, is one of the key factors behind the development of a so-called Japanese-style of guiding and diving.

Slate use not only defines the guiding style, but also the role of the dive guide, and has led divers to expect a kind of service not really found elsewhere.

On a more critical note, one could say that this type of approach, when pushed to the extreme, profoundly changes the approach to a dive, which becomes a more passive experience, and also reinforce reliance on the dive guide, which is not ideal for safety (we’ll discuss this in more detail here)

It would be interesting to trace back the origins of this now solidly implanted tendency to favour magnetic slates while guiding in Japan.

We believe big-slate use mostly came from Honshū’s Izu Peninsula, where diving conditions are forgiving, and the area offers a fantastic range of interesting endemic or rare macro critters, along with very experienced local divers and photographers, who dive as much as they can.

This probably led both to some specialisation of guides and returning divers and to the use of slates as an extension of underwater communication, which in turn became a symbol of expertise and spread, as expected superior customer service, to different areas around Japan and even overseas – if you have more info on the history and generalisation underwater slate use by guides in Japan, do let us know!

To end on a related note – interestingly enough, in a such service focused culture, the Indonesian liveaboard tradition of having guides create, on the spot, elaborate hand-drawn dive sites maps on slates to support their briefings (tradition which supposedly came from Egyptian liveaboards) does not seem to have caught on as in Japan, where the focus seems more on underwater communication and logbooks.