Culture

Japanese dive Culture

DIVING “JAPANESE STYLE”?

As a non-Japanese speaker and/or foreigner, you might not encounter this while diving in Japan, as service given by Japanese operators will most likely be adapted to what is perceived as your interests and needs as a non-Japanese diver.

And yet, we think it interesting to know that Japanese guides, operators and divers often state, sometimes quite proudly, that there is a Japanese style of diving, which is distinct from diving experiences offered elsewhere.

We’ve heard this discussed many times in a Japanese environment, taken part in discussions on the subject, which even popped up in major Japanese diving publications such as Marine Diving, where articles discussed what was special about Japanese diving, especially the Japanese way of guiding divers underwater.

Dive guide in action:“this snake eel’s head is protruding from the sand”

To be fair, this is hardly surprising. While all countries adapt things and practices to the needs and practicalities of their culture, in Japan, it seems modification made are greatly amplified by the echo chambers of the country’s relative isolation, often resulting in a strong Japanisation.

And many Japanese love to pick out such differences, whether real or imagined.

This tendency, which probably has to do with the complexities of Japanese identity, is often coupled with a slightly chauvinistic obsession with a Japanese way of doing things, which is invariably slightly different, and, as often implied, better or more advanced.

Digging a little deeper, this is something which can be traced back to the once highly popular theories on Japanese-ness, the Nihonji-ron, or, if one should want to go as far as the, to Japanese nativism of the early 19th century or even the Mitogaku – all this to say, nothing new under the (rising) sun…

And while it’s certainly true for say Japan’s take on Chinese noodles (the now world-famous ramen and chūka soba, which definitely evolved into something of their own in Japan, where they’d been imported over a century ago, mostly by people who had worked in Japan’s Manchurian colonies), and somewhat much less convincing when it comes to other aspects, it is true that there is something quite unique about Japan’s scuba-diving culture.

It’s not so much diving technique itself, which is quite standard, or the equipment used, but mostly concerns the role of dive guides and the service they offer, which cater to specific interests shared by many Japanese divers, along with certain underwater practices less commonly found elsewhere…

Another aspect is the relative isolation of Japanese diving culture, mostly due to language, and more social aspects such as its integration within the general hierarchical framework underpinning social interactions in Japan – which tends to make the culture more resistant to change.

Large magnetic slate used underwater

SPECIFIC INTERESTS

Diving is diving, right?

Kit up, go down, watch fish, go up and don’t die (too much paperwork…), as the joke goes…

And yet Japanese diving definitely does present certain specificities when it comes to diver interests, which in turn feed and shape a distinctive local guiding style.

Local, endemic species

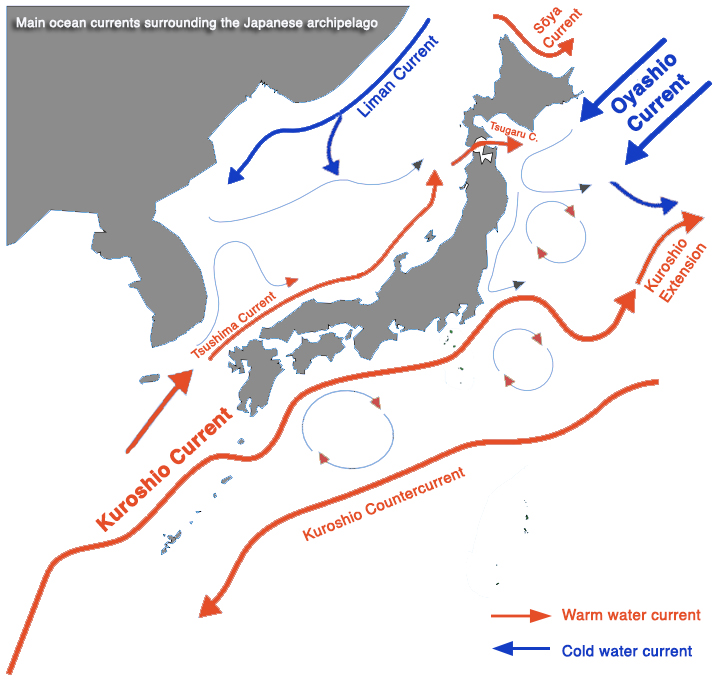

Some areas in Japan offer a high degree of endemism, due to several factors, among which we find the physical isolation of certain islands (such as the Nanpō Archipelago’s Ogasawara/Bonin islands, that were never connected to any landmass), Japan’s climate range and also specific exposure to currents.

Branches of the Kuroshio warm current bring warm water and tropical to subtropical species to what would otherwise be definitely cool and temperate waters, and this has a strong influence on Japan’s underwater fauna and flora (more on this here)

And Japanese divers are often quite interested in these local, endemic species – quite similarly Japanese domestic and even international tourists tend to have a strong interest in localism, the “local highlights” – including local food delights (some of which can only be sold locally, products labelled chihō gentei 地方限定 in Japanese).

While interest in local delights and iconic endemic species is shared with many non-Japanese divers, it does, however, extend to species that are slightly less popular outside Japan, outside the world of divers that are true fish-enthusiasts or foster specific interests in marine biology.

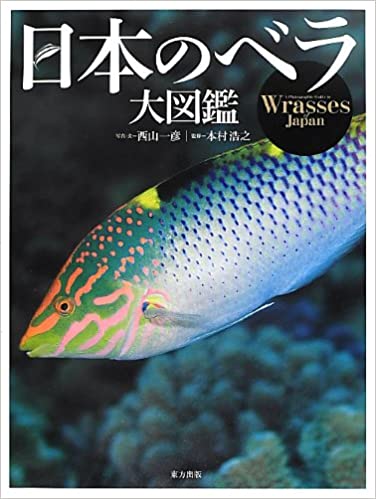

While all divers would love to see zebra sharks, Bobbit worms or even a wunderpus, Japanese divers are also generally more interested and knowledgeable than their non-Japanese counterparts about smaller reef fish such as damsels and anthias, butterflyfish, angelfish or wrasses, which are more of a specialist interest outside Japan, and often seen as more part of a reef’s ambiance than a highlight.

“Wrasses of Japan” – Image source: amazon.co.jp

Even in the professional dive-guide world, while some of us dive-pros are true macro-fanatics and often quite good on their nudibranchs, not many guides have more than basic knowledge of the smaller reef fish.

There are exceptions, of course, including photographers hunting down flasher-wrasses, but as a rule damselfish are not given as much attention as they are in Japanese contexts.

And yet – we’ve seen Japanese photographers dive to 40m specifically to shoot rare endemic anthias in Thailand for instance, led by the area’s expert guide (a recognised photographer himself). Their whole dive was basically planned around this. Reef fish really matter!

A good Japanese example of such an iconic endemic local species that delights divers would be the Yuzen or Wrought-iron butterflyfish (Chaetodon daedalma) endemic to specific areas of Japan, primarily the Nanpō Archipelago’s Izu and Ogasawara/Bonin islands.

It is definitely considered a local diving highlight.

Yuzen / Wrought-iron butterflyfish – Image source: blog.goo.ne.jp

Because of these interests, Japanese dive guides will generally have a much deeper, specialist knowledge of local species, and will resent not being able to identify a local fish, no matter how small.

Part of working as a guide in a Japanese context means learning, in depth, about the local environment, to be able to adapt to the specialist needs and questions of guests and photographers.

While this is true in almost any context, Japanese dive centres can really take this training a step beyond, with the apprentice-dive guide being in an almost disciple-like relationship with the highly knowledgeable local expert guide, sometimes called a charisma-guide, ie a charismatic expert, acting as an ambassador to the environment they represent (more on this here).

Colours and local variations

Another important Japanese interest is colours, fish colours, but also water colour (of which Japan’s famous XYZ Blue areas are a good example), coral of course but also distinct patches of seagrass, anemones, rocks, you name it.

This is highly linked to the somewhat mainstream photographic style found in Japanese diving publications, on the blog and photo updates of local dive centres, and the expos of well-known Japanese underwater photographers.

These pictures showcased are often more saturated and vivid than the works of non-Japanese counterparts, to the point of being somewhat abstract, some pictures featuring vibrant close-ups and blurring, to the point of almost becoming some sort of underwater impressionism or expressionism, forming a style of its own, now rather mainstream in Japan yet rarely found elsewhere (you can discover the works of some Japanese underwater photographers videographers here).

Image source: amazon.co.jp sample page from Sunday Morning – A Day Off With Nudibranches, by Yasuaki Kagii .

Beyond the works of such acclaimed Japanese underwater photographers, colours do speak volumes to Japanese divers, especially when combined with the interest in local, endemic and/or iconic species previously mentioned.

So do fish that are basically the same as the ones found back home, but with small variations in colours, patterns or shapes, local specificities which often drift over the heads of non-Japanese guests as they require both good knowledge of one’s local species, and also a real interest in such differences, even when other local highlights include massive schools of barracudas and giant “oceanic” manta rays…

When we were working on Thailand’s Andaman Sea, Japanese guests would be strongly interested in fish similar to what they knew from their local diving in Japan, yet differing slightly in their features and colours, and really keen on snapping pictures of these smaller reef fish, that otherwise simply didn’t interest non-Japanese guests as much.

On such highlight was the local endemic version of the red saddleback anemone fish (Amphiprion ephippium) for instance, that always got a warm welcome when introduced, far more than the usual not-so-interested ok that we got from non-Japanese divers.

Image source: www.thaich.net

Juveniles

Interest in the powerful combination of cute or beautiful juvenile forms (such as distinctive shapes and colours of juvenile batfish or the beautiful blue patterns of juvenile emperor angelfish) is quite common in the dive world, but some Japanese guides also take this knowledge one step beyond, combining spotting with solid information on the growth/life cycle of the species.

Indeed, Japanese dive guides are often more knowledgeable about juveniles forms of local species than their non-Japanese counterparts, more specialist knowledge which also derives from the generally deeper interest in the biology of local species found amongst Japanese divers and/or photographers.

Juvenile lion-fish

Gobies and blennies

We cannot mention Japanese diving culture and interest without mentioning gobies and blennies (haze and ginpo in Japanese)

Friends of ours working the Komodo to Raja Ampat routes on a famous Indonesian liveaboard, knowing that we worked we Japanese divers, often mentioned this about chartered groups of Japanese divers they sometimes hosted.

In places like Raja Ampat, with schools of schools of schools of fish flowing over your head like nowhere else, what is this thing Japanese divers seem to be having with…. gobies?

Blenny – Image source: tsuriwalker.com/ginpo

It’s true that gobies and blennies are highly popular in Japan. And while it’s certainly true that there are many blenny-fanatics outside Japan (hello Anna & Ned DeLoach of www.blennywatcher.com!), and that some blennies/gobies are indeed quite wild (we had great fun spotting highly territorial Gulf signal blennies in La Paz, Mexico), they are somewhat more of a specialist interest, and primarily focused on highly photogenic species.

Goby

Blennies and gobies are big in the Japanese dive world.

And it does help that Japan offers an amazing selection of the critters, including some great looking and rare ones.

Another link might be the recently abdicated Emperor Akihito, a keen ichthyologist who has published 30 scientific papers on gobies, and even has one goby named after him.

Naturally, Japanese guides are usually very knowledgeable on local gobies and blennies, often with behavioural tips on how to approach sometimes-elusive specimens.

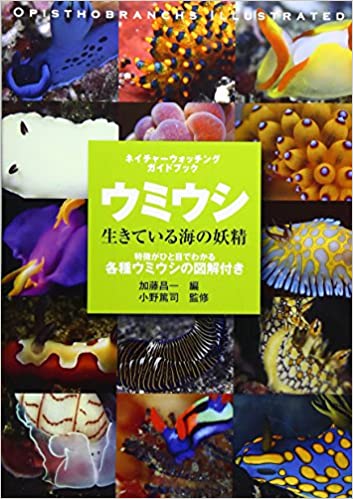

Nudibranchs (umi-ushi, ie “sea-cow” in Japanese, just like the dugongs…) are also very popular highlights in Japan, a country offers amazing, highlight photogenic and rare specimens especially in central Honshū and Okinawa.

However, non-Japanese diving cultures also have a good share of nudibranchs addicts, including proper fanatics, dive professionals and photographers.

Because of this, we wouldn’t really call nudi-love, as intense as it is in Japan, a true defining trait of Japanese dive culture…

Flabellina nudibranch

Image source: Opistobranchs Illustrated – Living Fairies of the Sea

And yet the (picture) “collector” mentality, common to insect maniacs and bird watchers, is quite common amongst Japanese divers and/or photographers, so get ready to learn something if you dive with sea slug enthusiasts in Japan.

“Cute” species and more

Not going as far as bringing up the timeworn notion of “kawaii” aesthetics into diving (going from plush keychains to underwater marine life is something a stretch), there is indeed a strong affection for “cute” species in Japan – something which is also true in other Asian countries.

Quite a few emblematic/iconic species highly appreciated by Japanese divers include critters or fish that definitely fit the “cute” category in a rather traditional, kitten-cute sense of the complex word (appealing and delightful, in a charming way especially something or someone small or young).

The adjective is widely applied to charming, small-sized/tiny species (boxfish!) and juveniles, but also, in a slightly the more local sense, to critters who’s cuteness is defined by odd or exaggerated features, basically slightly grotesque-looking fish.

Think lumpsuckers (Cyclopteridae) and frogfish, and basically all fish with big eyes, round or uncommon shapes, smile-like or dopey-looking features, other weird, comical traits such as being clumsy in their movements, not unlike the plush mascots and other “ yuru-chara” found everywhere in Japan…

And when a “cute” critter happens to be quite rare and/or local, its popularity rises sky-high.

A good example of a rather cute fish very popular in Japan is the longnose hawkfish (Oxycirrhites typus “kuda gonbe” in Japanese), which is a good example of a rather local Japanese obsession.

Longnose hawkfish are quite common in the Red Sea and elsewhere, including on certain sites where we worked in La Paz, Mexico (Fang-Ming wreck), much to the delight of our Japanese guests, whereas they rarely did more than raise an eyebrow with other nationalities…

Underwater quirks and oddities

Japan has its share of underwater oddities – while some are natural, like Japan’s underwater hot springs (Shikine in the Izu islands), are found elsewhere when diving in countries located on the Ring of Fire (famous Indonesian examples being found in Bangka and Weh islands, or around the Sangeang volcano near Komodo NP), others are more distinctively local, like an underwater shrine, said to be the only one in the world (Hasama Underwater Garden, Tateyama, Chiba Pref.), or underwater mail boxes like those found in Wakayama Prefecture’s Susami Bay or Okinawa main island’s 5 Sunabe No.1 dive site, and more.

Many people will also have heard of this Japanese diver’s 25 year-long friendship with a sheepshead wrasse in Tateyama Bay that went viral on social media a while back, but it is far from the only story of its kind…

Japan, and Japanese dive culture, is just full of colourful character and stories, including famous underwater mascots like Tokunoshima’s (Amami islands), famous green turtle with a mountain-shaped shell nicknamed Yama-chan (Yama = mountain in Japanese), that has been entertaining divers in the shallows for over 10 years….