Underwater Japan

An introduction to the Japanese underwater world

JAPAN AS A DIVING DESTINATION

Japan is often said to be a land of contrasts.

And indeed, while famous for massive, hypermodern and often slightly hectic cities for instance, as soon as one ventures out of the Pacific-Belt megalopolis, Japan also turns out to be a true nature-lover’s haven, home to an incredible array of landscapes and natural wonders where one can feel the power of the elements…

And this goes for both above and below the surface.

Tōkyō – Image source: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images

On land, you’ll find breathtaking sceneries, volcanic peaks and unavoidable mountains with extensive forest-coverage and rich in wildlife.

And underwater, as an island nation made up of almost 7,000 islands and with nearly 34,000 km of coastline, Japan also offers a spectacular variety of diving options, to the point that the archipelago has sometimes even been called one of scuba-diving’s best-kept secret in recent promotional material.

A secret?

Only to a certain point – but it is definitely is true that Japan is not generally acknowledged as one of the major scuba diving destinations in Asia, where south-eastern, tropical countries such as Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines or Malaysia garner the most of the international diving community’s attention.

And even in Japan itself, mention scuba diving and most people will think only of the subtropical southern islands of Okinawa – precisely because they offer conditions closer to those of the South-East Asian countries just mentioned…

However, with its vast size and relative land to sea ratio, Japan actually has great dive spots spread across the length of its coastline– and beyond the islands of Okinawa, the country holds many underrated gems, including some world-class highlights in the country’s more temperate waters, off the coasts of the main island of Honshū for instance…

It is undeniable that diving places like South-East Asia’s Coral Triangle is an incredible experience, and that Japan’s subtropical-style diving on coral reefs, as pretty as they are, can’t really compete with places like Komodo or Raja Ampat…

Yet it is also true that for divers not exclusively focused on warm water diving, the still relatively unknown Japanese waters really have a lot going on for themselves, offering a rare richness and diversity, with contrasting conditions that are often way more dynamic and diverse than the relative uniformity of South-East Asian tropical diving…

Yonaguni “Monument” – Okinawa Prefecture – Image source: Naotomo Umewaka

A complex environment

Japan has, on many levels, a reputation as a somewhat complex country.

This complexity definitely extends to its geographical features and marine environment, which offer prospective divers a range of conditions rarely found elsewhere…

The key word for Japanese diving is probably variety, as it is truly rare that one single country can offer so much diversity underwater.

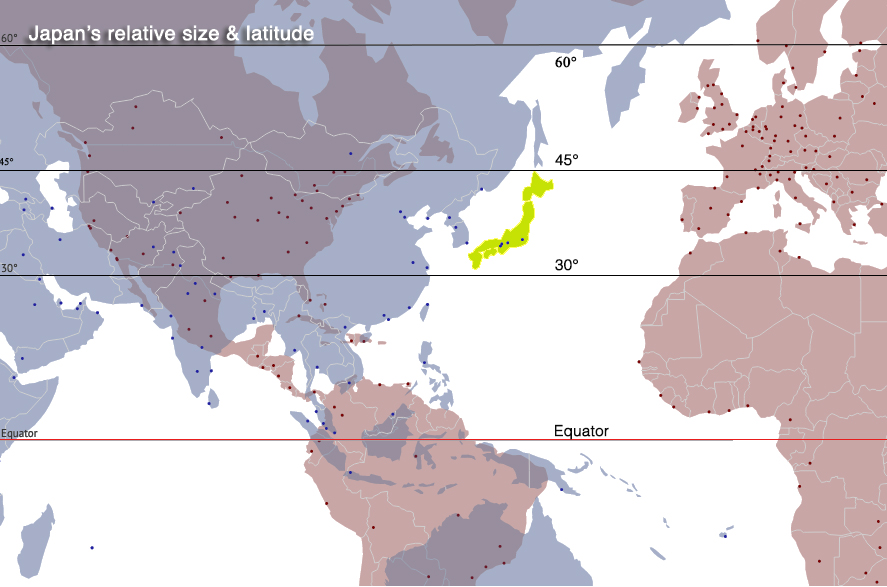

And just looking at a map of Japan, highlighting the country’s unique profile and geographical position, is enough to give an idea as to why this might be the case…

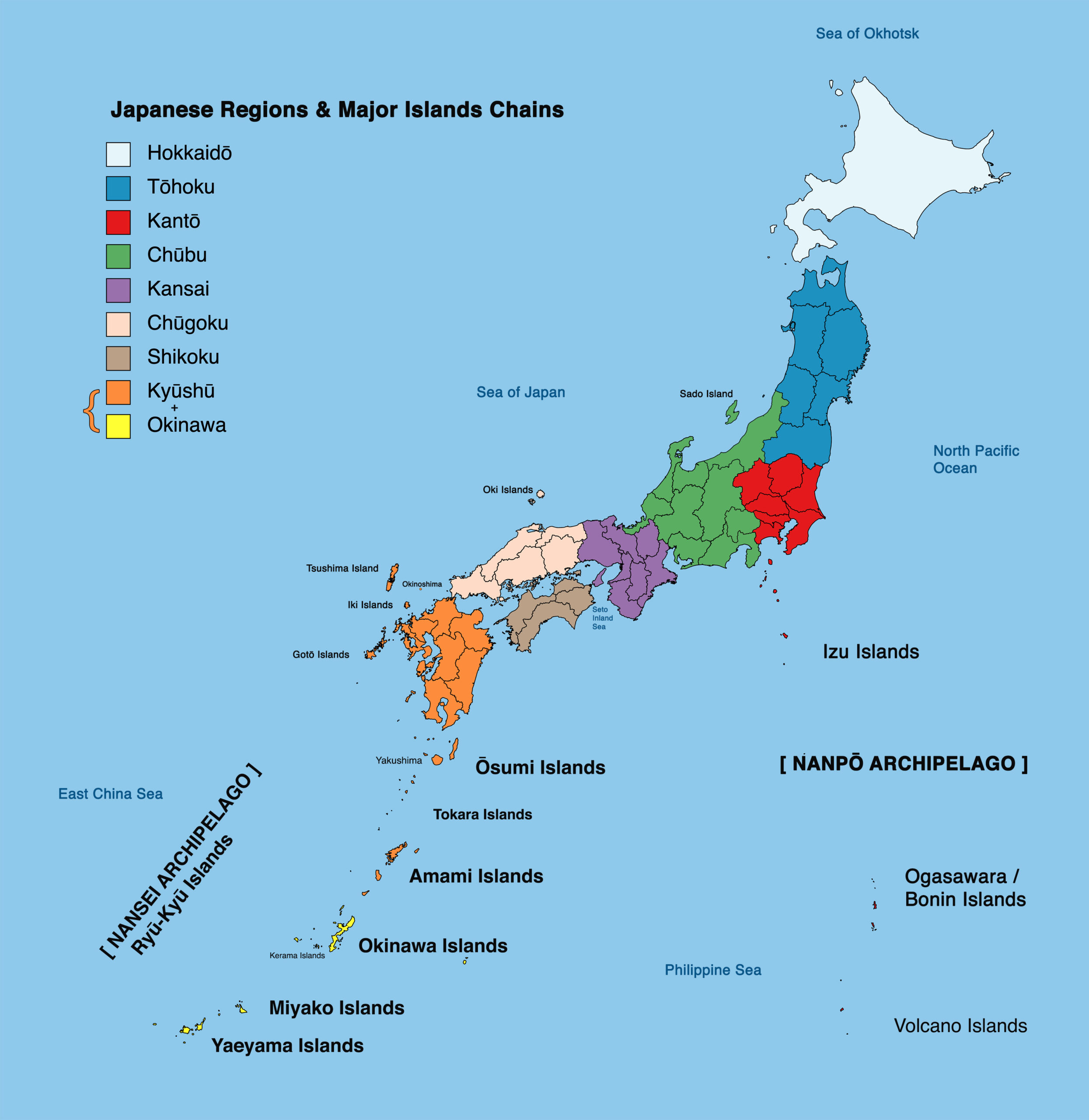

As mentioned, Japan is an island-nation stretching over 3,000 km, with extreme latitudes and conditions ranging from subarctic north to a strongly subtropical far south.

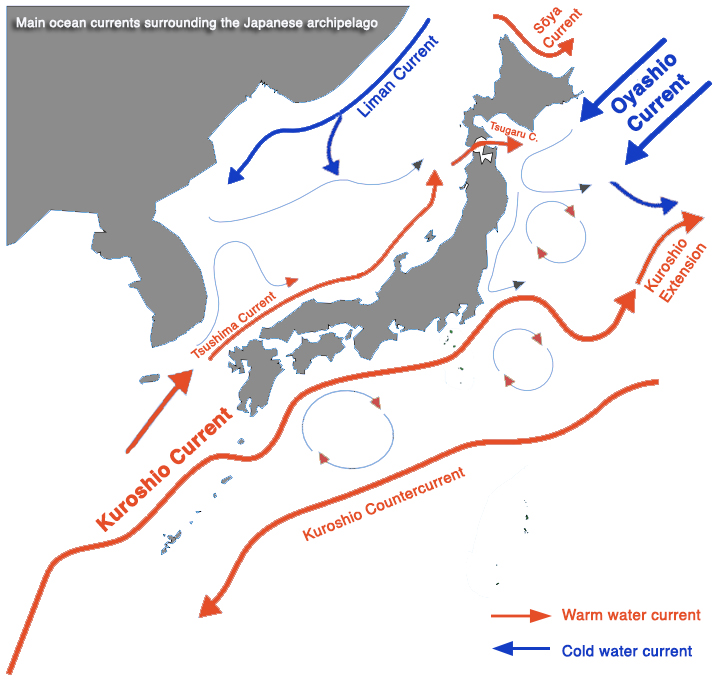

Along with this unique geographical position and the a vast distance between its colder northernmost islands (Hokkaidō) and warmer southernmost islands (Okinawa), Japanese coasts are also exposed to key warm and cold-water currents and a wide seasonal temperature ranges.

All this contributes to give Japanese waters their extraordinary diversity, each area having its own unique underwater fauna, flora and coastal ecosystems, and offering rich and varied diving environments.

Contrasting conditions

Japan has three main marine ecosystems, which are also subject to strong seasonal variations.

This means that water temperatures, environments and marine life vary greatly.

SOUTHERN JAPAN

In the south, the crystal-clear and warm water of Japan’s subtropical islands offer shallow sloping coral reefs, drops-offs and walls, volcanic and limestone topography and/or picturesque subtropical beaches with palm trees, that have little to envy to their more tropical cousins…

This southern region (notably the Nansei islands south of Kyūshū and the southern Nanpō islands) allows for – weather permitting – year-round subtropical diving.

The warmest waters are found in the Ryū-Kyū islands (Okinawa region), where water temperatures rarely drop below 20°C in the coldest months, allowing for 5/7 mm diving in winter, and in the summer months, 3mm to no-wetsuit diving, as some areas reaching 29°C or more.

Other southern areas will be much cooler in winter, but reach similar temperatures in the summer months.

Aka-jima – Kerama Islands, Okinawa Prefecture – Image source: okinawaclip.com

CENTRAL JAPAN

The central part of Japan offers a large variety of seasonal conditions, with generally more temperate waters that warm up in the summer months.

Underwater, there is primarily rocky topography, with coral reefs in the warmer areas along with seaweed seafloors, and even kelp forests in more northern areas.

The water of central Japan, where powerful warm and cold-water currents merge, are subject to intense coastal upwellings, that give the area its rich and complex marine life, and offer divers the chance to encounter both amazing macro subjects and larger creatures.

In central Honshū, water temperatures fluctuate from roughly 10°C in winter to 27°C in summer.

This means that there is a definite drysuit season covering the winter months, where water temperatures range between 10°C to 15°C and the air is 10°C or less, which eases into more comfortable wetsuit diving season when the temperatures reach 20°C+, usually from spring onwards (depending on both weather and the movements and strength of the Kuroshio warm water current).

In some areas, waters can also get very warm in the summer months, rivaling those of southern regions.

Izu Peninsula – Shizuoka Prefecture – Image source: japan-magazine.jnto.go.jp

NORTHERN JAPAN

And Japan’s subarctic far-north offers much colder conditions all year round, where giant octopus and king crab lurk in the deep, and even the possibility to dive under ice floats seasonally…

Waters rarely reach above 20°C+ in Hokkaidō, and drop to freezing temperatures in winter, meaning it is primarily cool water (primarily drysuit) diving most months, and even ice diving in the winter.

Shakotan Peninsula – Hokkaidō Prefecture – Image source: dronestagr.am

Outstanding topography and blue waters

Japan is primarily a stratovolcanic archipelago located at the meeting point of important tectonic plates, with strong seismic and volcanic activity to this day. The country’s steep and rugged landforms are an indication that the Japanese islands are still, geologically speaking, a relatively young area.

These characteristics have shaped both Japan’s complex coastline (which also includes the glacier-formed inlets characteristic north-east Honshū’s ria coast) along with its underwater topography, which combines volcanic features and coral-based limestone.

Japan’s underwater topography is often nothing short of spectacular, offering divers odd-shaped rock formations, caves and underwater canyons, along with rugged limestone cliffs, and beaches with both fine white sand black volcanic sand beaches.

In actively volcanic areas such as Kyūshū, underwater remains of recent lava-flows, offering a truly dramatic diving, and changing environment.

Areas famous for their underwater landscapes include the Nanpō islands south of Tōkyō, coasts of Kyūshū and the Ryū-Kyū islands (which themselves are mostly peaks of submerged mountain ranges), where you’ll find Miyako-jima’s famous underwater caves, canyons and arches, or Okinawa main-island’s Blue Cave (more on the highlights of Japan’s underwater topography here)

Miyako-jima – Okinawa Prefecture – Image source: miyakojima-style.jp

Japan’s volcanism means it is also possible to dive underwater hot springs in some areas (Hokkawa in Shizuoka prefecture, Shikine-jima in the Izu islands or Taketomi in the Yaeyama islands, for instance).

As a side-note, Japan’s Yonaguni island is home to a world-famous geological curiosity, the “Yonaguni Monument” or Yonaguni Submarine Topography, massive monolithic rock formations of very fine sandstones and mudstones.

The formations look somewhat man-made, and have been the subject of passionate pseudo-archaeological speculation since their discovery.

Beyond remarkable topography, Japanese waters offer, in season, outstanding visibility, sometimes reaching 30m+, and with beautiful blue hues.

This is why many diving areas in Japan will refer to the colours of their famous aqua/turquoise/emerald-blue waters as something blue, such as Hokkaidō’s Shakotan Blue, the Nanpō archipelago’s Hachijō Blue of the Izu islands or the Bonin Blue of the Ogasawara islands, the western Izu Peninsula’s Ita Blue, the central Sea of Japan’s Echizen Blue, Wakayama’s Susami Blue, the Satsunan Island’s Yoron Blue and Okinawa’s Kerama Blue or Hateruma Blue, just to name a few…

Kerama Blue – Okinawa Prefecture – Image source: fun-japan.jp

Experience the power of nature

Despite the country’s ultramodern cities and infrastructure, one is still easily reminded of the power of the nature in Japan, and this is certainly holds true for Japanese marine environment.

Nature plays an important role in Japanese life, both culturally, as illustrated by the animistic/agrarian aspects that remain in Japan’s shintō religion, but also for purely practical reasons, in a country comprising such climatic extremes.

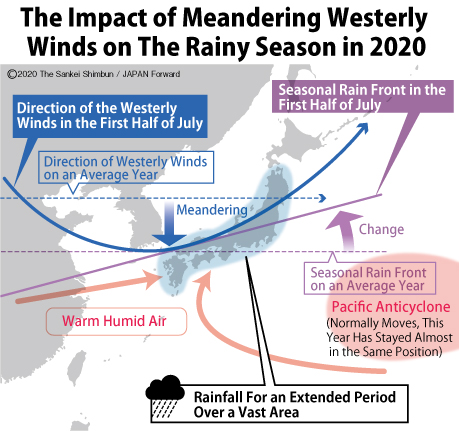

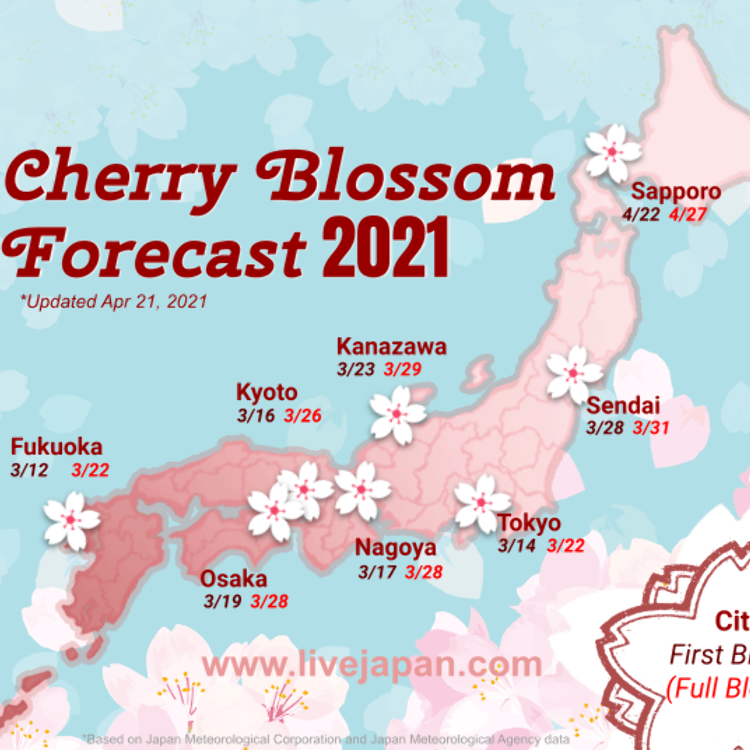

Japan has strongly marked seasonal changes, including various “fronts” sweeping up the country, such as the “cherry blossom front” or the “rainy season front”, and the seas and coasts of Japan also witness the seasonal “arrival” of more powerful flows of the Kuroshio warm current that affect water tempearatures and marine life.

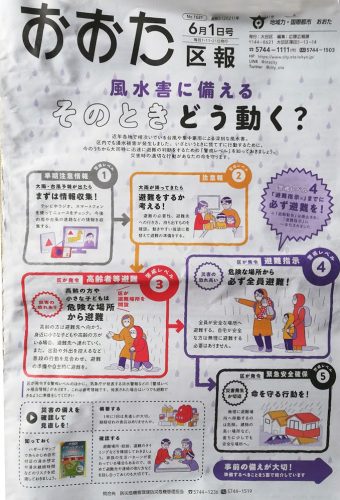

Preparing for flooding risks –

Source: Ōta district information sheet, Tōkyō city

Rains… Image source: japan-forward.com

Cherry blossom front – Image source: livejapan.com

Japanese daily news is full of reports of extreme temperatures, heavy rains (including “guerrilla downpours”) and snowfall, floods, landslides, typhoons and other storms, and not to forget the unavoidable earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or tsunamis…

“Guerilla downpour” – Image source: www.news24.jp

For a maritime country, Japan has a highly mountainous landscape, with massive forest coverage and many regions that were still, until recent times, highly isolated from the major population concentrations gathered along the Pacific coast, and remain lightly populated to this day.

It might, however, be difficult to find areas completely devoid of human intervention, as the long stretching coastlines and deep forests were for the most part transformed by millennia of human activities and exploitation, ranging from intensive forestry to coastal fishing ports and the now unavoidable concrete protection of tetrapods, seawalls and other dykes, so commonly found on Japanese coastlines…

Tomonoura, Seto Inland Sea, Hiroshima Prefecture – Image source: wikipedia.org

And yet in many ways, Japan is still a very “wild” country, or rather a place where you can easily get a feel of the strength of its generous nature.

The contrasting ecosystems induced by the country’s wide latitude shape the landscape and the seas, and are subject to marked seasonal changes.

Furthermore, Japan’s strategic buffer position between the north-east of Eurasian continent and the Pacific ocean means it is exposed to both cold and hot water currents including the powerful Kuroshio, Pacific equivalent to the Atlantic’s Gulf Stream), flowing up to 3 knots (!) along the coasts of Japan…

The direct action of the major hot and cold water currents making up the Kuroshio-Oyashio system, induce temperature changes, cold water upwellings, spawning and feeding cycles, along with marine life migration events, and bless Japanese waters with extensive marine resources.

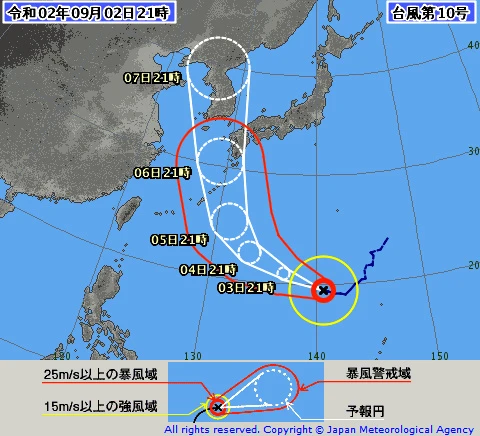

In the summer months, cyclonic storms (typhoons) sweep the southern islands, and winter months can bring heavy snowfall even on the seashore, along with freezing events and drifting ice floats in the far north.

Typhoon no. 10, 2020 – Image source: asahi.com

Japan’s geological position, at the meeting of major tectonic plates, accounts for the country’s famous seismic and volcanic activity, and its largely stratovolcanic topography.

Both land and sea are often rocked by earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, reshaping the underwater environment, and even giving birth to new islands, such as Nishi-no-shima, in the south of the Nanpō islands.

Originally an underwater caldera, the island first expanded massively out of the water after an eruption in November 2013, and its landmass is still growing to this day…

Tsunamis, or tidal waves, are also well known force affecting Japanese coasts, such as, most recently, the tsunami that devastated the Pacific coast of Tōhoku on March 11 2011, causing much loss of life and destruction.

Sanriku Coast after the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami – Image source: .japan-guide.com

We would like to salute the outstanding efforts of a friend and former colleague of ours, Hiroshi Satō / Kuma-san, who has been actively involved in coordinating volunteer activities of underwater recovery, cleaning and environmental rehabilitation of his local Iwate waters ever since the 2011 tsunami hit.

You can read more about the activities of the Sanriku Volunteer Divers here.

Diving, diving everywhere…

Japan’s specific geography, as an island-nation where no point in the country is more than 150 km from the sea, means that diving is found nearly everywhere, and over 2000 dive spots across listed across the archipelago.

Shore diving access – Image source: maple-h.co.jp

Shore diving access – Image source: marineclub-an.com

The spots includes numerous shore-diving options, local shore diving being the most commonly found form of local diving on the rocky shores of the main islands, with active fisheries off-shore.

These shore diving sites, especially the ones close to or actually on the Pacific-Belt Megalopolis, are often setup for diving, with easy-access parking areas, handrails and entry-ropes, and sometimes even showers to rinse off salt water after a dive…

Let’s say this is one of the positive sides of the omnipresent concrete landscaping of Japanese shorelines…

That said, some shore-diving spots are a little wilder and quite difficult to reach without local knowledge.

Japan also offers good lake diving options.

Boat diving is also very common, especially in southern islands.

This is mostly done fron comfortable, dedicated boats, cruising at speed to nearby dive sites or more remote ones in some cases.

In more remote areas however, boat diving might be done from more simple converted fishing vessels.

Liveaboard diving is almost inexistent, with the recent exception of some short semi-private cruises recently organised around Okinawan islands for photographers and videographers.

Read more on Japan’s diving options here.

Accessibility:

your mileage may vary…

Diving options abound all around Japan, but accessibility varies greatly.

The most accessible dive sites are those situated close to Honshū’s Pacific-Belt cities and accessible through Japan’s extensive rail coverage, especially closer to Tōkyō, including the Izu Peninsula.

Another major, largely accessible diving area is the Okinawa region, especially the islands close to major airports such as the main island of Okinawa or Ishigaki, both of which have international airports.

More remote destination are found either in less developed and rural areas, often at the periphery of the main islands, or isolated by Japan’s mountainous topography, which directly affects transport options.

Kagoshima Prefecture, at the southern tip of Kyūshū, was only fully linked to the Shinkansen bullet-train network in 2011, for instance.

But the most common reason making access difficult is simply the sea.

Japan is an island-nation, and while maritime networks are usually quite efficient and reliable (especially compared to South-East Asian ferries), some major diving islands are definitely more difficult to reach than others – the perfect example being the Ogasawara/Bonin islands group, south of the Nanpō archipelago, which are only accessible through a 25-hour ferry ride, leaving weekly from Tōkyō…

Other remote islands with a strong diving activity, such as the Izu or Satsunan islands, sit somewhere in between, offering varying degree of accessibility, ranging from daily flights, hydrofoils and speed-ferries, or slower local ferries.

Ogasawara ferry route – Image source: travelyourway.net/discover-ogasawara-islands

Remote islands

Japan has 6,852 islands (here defined as a land mass of more than 100 m in circumference and surrounded by water), with roughly 430 inhabited islands, including the 5 main landmasses.

The remoter of these inhabited islands are called Ritō 離島 in Japanese, which is actually an official administrative status, granting access to certain governmental subsidies or specific postal rates for instance.

It’s important to understand that the islands’ degree of isolation is not exclusively based on distance from a “mainland” of sorts.

While some islands are indeed physically very distant from the main islands, others, such as the islands of the Seto Inland Sea for instance, are way closer, and yet still classified as being “remote”.

Current classification criteria are as follows:

Remote islands must be inhabited, and have a population of over 100 inhabitants.

They must be separated from a major coastline by more than 5 km of open-sea, and not connected by a land bridge.

Finally, maritime connections must be less than 3 ships per day.

We’d like to add that Japan’s remote islands can offer fantastic diving, and often access to marine life more difficult to encounter elsewhere, along with singular natural and cultural highlights. Japan’s remote islands are definitely worth the effort to get there!

Some basic info on Japan’s remote islands and their culture is available here.

Nanpō islands ferry connections – Image source: www.kouwan.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/rito/island/

And a slight culture shock…

Diving in Japan is not only unique because of the remarkable physical diversity offered by the country’s waters, but also because of Japan’s diving culture.

Indeed, as with many other aspects, things are often done a little differently in Japan, and dive culture is no exception.

In Japan, the term “island nation”(島国 shima-guni in Japanese), is often used to stress an implicit physical isolation of Japan, as a source of cultural singularity.

You’ll also commonly come across the notion of an island-nation mentality, concept referring to a supposed “Japanese national character”, seen as the product of a self-contained society, physically isolated from others by the surroundings seas…

Whatever truth might be behind this idea (the sea is also a powerful communication route…), it is undeniable that Japan is indeed a nation of islands where the sea played, to this day, a crucial role in shaping the country’s history and economy, and still largely pervades its entire culture.

When it comes to the modern age of scuba-diving, however, it is not so much the fabled physical separation, as long decades of relative isolation offered by the Japanese language that have allowed Japan to develop its own distinctive blend of dive culture.

Underwater slates and flags – Image source: akasyachi.com

While sharing the same common foundations as European diving (sharing some aspects of the closed “club mentality” found in continental countries such as France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and also in the UK), and also under the powerful influence of North-American (W)RSTC standards for dive education and general organisation, Japanese diving has over the years developed its own codes and specialised interests.

Furthermore, scuba-diving activities and associated activities are often found in a complex equilibrium with local fishing activities, quite different from what is found elsewhere.

As an example, one of the most outstanding aspects of Japanese diving can be found in the role of the dive-guide who will normally be guiding in a way referred to (with an undeniable hint of pride) as Japanese-style.

More details on this here.

While a non-Japanese speaker might not necessarily encounter this Japanese-style when diving in Japan, this is just one of many examples of how diving, as most things in Japan, is certainly similar but also a little different, often with little extras, which offers a refreshing change from the relative cultural uniformity of say, the South-East Asian diving industry…

And since we’re on the subject of culture, a country like Japan has, needless to say, an amazing after-dive culture. After your gear is rinsed and hung-up to dry and you’ve showered, you are, after all, in Japan.

Food. Drink. Laughs. Sharing and all the rest…

Diving in Japan, especially in a Japanese context, can often be a gateway to a slightly more intimate Japan than what most non-diving tourists get to experience…

And let’s not forget Japanese hot-springs (after off-gassing some of that nitrogen, of course, safety-first…) are definitely the way to warm up and/or unwind after a hard day’s diving!

After-dive hotspring, Futo, Izu Peninsula – Image source: namidea.com