Culture

Elements of Japanese Diving History

The Ama

Image source: blueleaf.jp/20986.html

Japan's Professional freedivers

Japan is an island nation with a long fishing tradition, which includes professional freedivers.

There are two main traditions, traditional freediving spearfishing in the Okinawa region, somewhat similar to what is found elsewhere in the Pacific and, more famously, coastal communities of professional freedivers, most commonly known as the ama.

In modern times, ama diver are predominantly women, who dive daily on breath-hold to collect various types of seafood (abalone, oysters, seaweed and shellfish) and, with the late 19th century invention of pearl culture, also for pearls.

Image source: www.euronews.com

In the past, however, the word ama covered a broader range of sea-related activities, and included men and women, whereas ama culture is now moslty focused on women doing all the diving.

Men, especially spouses, do often play a role in the activities, such as tending the boat and helping the divers.

Image source: ukiyo-e.org

Though this is less well known, certain areas of still have a male ama diver tradition, such as the town of Shima, in Kansai’s Mie Prefecture.

Here is an interesting article on some of the last remaining male ama divers of Japan (roughly 320 divers in 2014).

From a technical point of view, all amas work on breath-hold. Early amas dived with no googles, then started using used low-volume diving goggles while freediving in the shallows.

These low-volume diving goggles, called mīkagan (ミーカガン) were developed in Okinawa in 1884 by Yasutarō Tamagusuku

Image source: Yoshinobu Nakamura 1962/63

Some of these goggles were fitted with pressure equalising mechanisms for use in deeper waters in the late 19th century, which recently became an inspiration for (high-tech) competitive freediving (no-limits) equipment.

Image source: Yoshinobu Nakamura 1962/63

Image source: divingfan.net

All ama divers now use diving masks (some are antiques) the most common being round single-windowed models, with no nose-pocket.

Amas also now all use fins and wetsuits, but still work on breath-hold.

Ama diving masks, Chiba Prefecture – Image source: heritagedetection.wordpress.com

Image source: osatsu.org/

Historically, early divers, even female, wore only a loin-cloth (fundoshi) or simple wraparound waist-cloth and usually no top while working.

However, in the 20th century, the female divers adopted swimsuits, and an all-white diving uniform in order to be more modest while diving, reflecting a changing moral codes.

This was followed by the introduction of wetsuits in the 1960s onwards, which increased time it was possible to work comfortably in the sea (water temperatures drop to 10°C in winter in Mie Prefecture, for instance).

Image source: www.kankomie.or.jp

Most of the remaining modern amas work in wetsuits, but some still choose to wear the traditional white garbs, especially in warmer weather, or for tourist or more ceremonial purposes.

Early amas used no mask, as seen on woodblock prints.

They then adopted goggles, first crude tortoise shell models then the Mīkagan type when these became largely available in the late 19th century.

Some adopted pressure equalising goggles, allowing for deeper dives, before switching to masks.

All amas now dive with a mask, usually a large single windowed, nose covering masks, but some use more modern models.

Amas do not use snorkels.

The image below, taken at the Toba Sea-Folk Museum, shows the evolution of underwater vision gear used by the ama, from googles to masks.

The second-last photo is interesting as, contrary to the illustration above, it actually shows a nose-encompassing mask fitted with pressure-equalisation bulbs, which is a little odd.

It’s difficult to see on the image but there seems to be a noce-clip-like device inside the mask, which might mean that the user was not able to equalise mask pressure by blowing into it, hence the bulbs…

Evolution of ama underwater vision equipement – Image source: www.diveoclock.com

Up to the mid-20th century ama divers also descended with no fins, but these were quickly adopted for confort, efficiency and safety.

For the freedivers out there, the amas have no set breathe up, but the final inhale, however, is mostly passive, with a small inhalation just before the dive, rather than a full breath.

Some amas even dive on an exhale in the shallows, a form of FRC diving, but most dive on inhales, especially for deeper dives.

They aim for relaxation during the dive, which makes sense, given their repetitive dives with short surface recovery times (60 seconds or so).

After a dive the amas, as well their haenyeo Korean counterparts, use a recovery breathing technique called isobue in Japanese (and sumbisori in Korean), which is a long and slow exhalation, with the upper lip drawn over the lower, creating a whistling sound (“sea whistle”).

This makes the diver’s presence known on the surface, and supposedly helps with recovery (perhaps purging the CO2 out on the exhale)

All amas are said to equalise hands-free (without pinching the nose – the most commonly used masks don’t have nose pockets), using a form of Voluntary Tubal Opening (VTO), most using the soft palate / root of the tongue to push the air to the eustachian tubes and equalise.

Image source: https://english.kyodonews.net

The ama are organised along an age and rand based hierarchy. The most experienced divers dive from a boat (funado), down to depth of 25 meters max, using a 20kg weight for rapid descent and usually pulled back up using a rope.

Less experienced divers (oyogido) swim out to shallow areas close to shore, diving to a maximum depth of 10 to 15 meters.

Image source: Cathay Pacific

Working dive times are usually around 30 seconds to a minute.

You might read articles mentioning 3 minute dives, but anyone with some experience of dynamic apnea and/or spearfishing knows that this is highly unrealistic, especially in a cold-water, working environment with many repetitive dives…

Surface intervalls are quite short, usually 60 seconds or so.

As an example the current 300 meter dynamic with fins world is in the 3 minute zone (in a pool!), and William Trubridge’s 224 meter free-immersion record is in the 4 minute zone – and these are performances of highly trained and professional athletes, with efficient streamlined/movements not older women searching for shells in cold water, and prying them off the seabed and collecting them…)

Remarkably, many ama divers continue diving into their 80s, something which is also found in the Jeju’s haenyeo professional freedivers.

The divers organise multiple diving sessions during the day, staying up to a total of 6 hours in the water when weather permits, collecting shells or dislodging them away from the rocks or seafloor with prying tools.

The activity is dwindling away, with an aging, limited population, but has witness a recent regain of interest as tourism attraction and local cultural heritage, and has been subject of TV series and documentaries.

Image source: Award winning photo by Kaho Wong, 2017

Names and etymology

In Japan, the term ama is the best-known term to designate what are now primarily female professional freedivers.

The word most like derives from a common root with the Japanese word for sea, umi – a commonly encountered explanation is that it derives from a contraction of ama-bito, written in sinograms as [海人], with the meaning “sea person”.

In more ancient times, the word covered people, male and female, involved not just in breath-hold collecting activities but generally in fishing and associated sea-based economic activities – which mirrors a similar word use in some Okinawan languages, uminchu, written with the same sinograms [海人], “sea person”), which does to this day covers people involved sea and fishing related activities.

Nowadays, the word ama is most commonly written with a sinogram combination reading “sea woman” [海女] , but another character, created in Japan, 塰, is sometimes also used.

(since their first introduction in the 5th century, sinogram use has always been very flexible in Japan, especially when used to write indigenous Japonic words).

Today, and in the recent past, the vast majority of ama divers are/were indeed women, but this was not always the case.

The word ama itself can also be written in a masculine form, with another sinogram combination, [海士], which can be read “sea man” or “sea specialist worker”.

Local variations also such as kaito in the Izu Peninsula area (Shizuoka Prefecture) for instance, and there are probably others to be found in the local dialects and languages of the archipelago, since ama diving cultures existed from northern Honshū to the southern Ryū-Kyū islands.

Image source: Abalone divers, Utamaro

History

The history of ama divers is clearly very ancient, speculated to be at least 2000 years old, but probably much older, given the importance of shell mounds ([貝塚] kaizuka ) from the middle-Jōmon period onwards, including some shells that were no doubt collected on breath-hold.

Freediving activities are also mentioned in the Gishi Wajin Den (魏志倭人伝), a Chinese description of the Japanese islands and their inhabitants, which dates back 285 CE.

Ama freedivers are first mentioned in literature in the oldest Japanese anthology of poetry, the Man’yōshū (759 CE) and in works of Japan’s Heian period.

Up to the mid-20th century, female ama divers worked in various levels of undress, which also led to female divers being a recurrent theme in woodblock prints, including many suggestive, erotically-charged representation.

Here are some of the more figurative works:

This tradition seems to have found something of an extension with mid-20th century photography.

A number of photos, mostly taken in the early 1960s, documenting ama diving activities.

These famous are pictures are mostly attributed to photographers Fosco Maraini, (Ishikawa Prefecture’s Hegura-jima, on the sea of Japan), Yoshiyuki Iwase (the Chiba Prefecture’s Iwawada coast ) and Yoshinobu Nakamura (all around Japan)

The contrast with modern, wetsuit-wearing amas is quite striking.

Looking a little more closely at some of these pictures, where most of the young women supposedly working half-naked have barely suntanned skin, whitened teeth and sometimes make-up, and given the time-frame (1960s…), there are reasons to believe that some might actually be professional models who came for a photoshoot in a traditional setting…

A Kuroshio-area freediving culture

It is important to keep in mind ama type divers, while commonly associated with Japan, are historically not an exclusively Japanese development.

Though they are not really encountered on the mainland today, there are ancient Chinese accounts describing similar diving professionals on the continental coast.

Image source: Wikimedia

Chinese pearl-diving, in Song Yingxing’s 1637 Tiangong Kaiwu encyclopedia of technology

More importantly, the Korean island of Jeju has, to this day, a very similar tradition of female freedivers, organised in a similar hierarchical structure, with similar religious practices and similar diving techniques, including the technique of whistling while recovering on the surface to speed up CO2 venting and O2 intake (called isobue in Japanese and sumbisori in Korean), and is a form of recovery breathing.

The Korean professional freedivers of Jeju are called haenyeo (written with the same sinogram combination reading “sea woman” [海女], as their Japanese counterparts).

Haenyeo women were involved against the Japanese during the colonial period, and have become a symbol of national pride in Korea, and seeking to highlight differences unfortunately does not help bridge research on these two obviously connected in the case of these two traditional diving cultures.

There was even was a form of competition between Korea and Japan when it came to registering this cultural asset with the UN, as illustrated by this article for instance. Here is a UNESCO video on the Jeju Island’s haenyeo culture, and here is a UN University documentary on Japan’s ama culture.

It seems very likely that ama–haenyeo-like freediving professional are neither an exclusively Japanese nor Korean developments, but rather a regional culture, shaped by conditions induced by the Kuroshio warm current.

While surviving traditions are found almost exclusively in Japan and Korea, historically breath-hold sea activities existed in different areas of the Kuroshio zone, including the islands of Japan and the Ryū-Kyū arc, along with different areas along continental coasts and the Korean Peninsula.

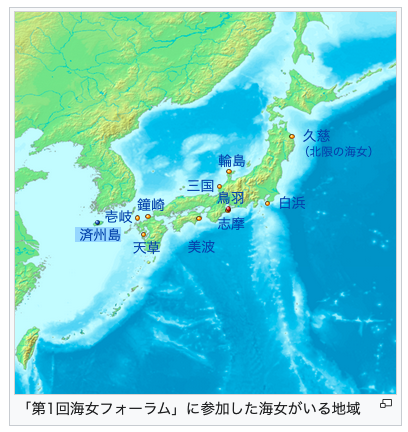

In Japan, ama divers are now mostly concentrated on the Pacific-coast of western Honshū, but were historically been active from Tōhoku’s Pacific coast to Okinawa, with strongest concentration of their activities being on the sea of Japan, and Central Japan and Kansai to Kyūshū.

Image source: bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages

Image source: www.furusato-tax.jp

Ama culture, past and present

Amas dived primarily to collect seafood (especially shells), seaweed, and, later, cultivated pearls.

After cultured pearls and pearl farming techniques were developed in Kansai in the late 19th century, along with the establishment of large aquaculture farms in western Japan, such as Toba’s Mikomoto Pearl Island, pearl collection became one of their primary activity, and actually increased the demand for ama-type divers, that were also recruited in Korea during the colonial period.

Pearl cultivation requires introducing an irritant into the oyster, and then placing the oyster in a safe place and checking in on it, before finally harvesting, operations in which ama breath-hold divers were the most useful workforce, though hard-hat divers were also used.

The specificities of pearl culture also led to the development of the lightweight Ohgushi Respirator unit, which could be used tethered or self-contained.

In the 1940s, roughly 6000 amas were reported to be active along the coasts of Japan whereas today amas are estimated at less than 70 divers per generation, and are increasingly turning into a tourist attraction.

However, the divers still have practical use for regulated seafood collection activities, to maintain sustainable fisheries.

Image source: jokuti.blog.hu

The amas traditionally formed a close-knit society, sharing communal drying out timesin work-huts (amagoya), and had their own codes and religious rituals.

However the recent development of ama tourism, while trying to maintain ama local traditions and present them to the outside world, is also introducing many changes to what is left of these women’s traditional practices, as is usually the case when a cultural tradition evolves into a folklore.

The centre of ama tourism is Kansai’s Mie prefecture, especially the Ise-shima peninsula area, which features attractions such as the Mikimoto pearl island and museum, the Toba Sea Folk Museum, and more.

It is also possible to book and ama hut experience, to taste fresh local charcoaled-grilled seafood and get meet the divers in between dives, and even get wet and freedive with ama divers.

Modern freediver Emily Corinne Tucker went to dive with amas in Mie Prefecture in 2015, this is her report on the Deeperblue.com forum

Image source: www.jldb.bunka.go.jp

To conclude on a rather interesting anecdote, freediver Jacques Mayol, who single-handedly invented the modern approach to freediving, and of The Big Blue movie fame, was born in Shanghai, where he grew up (and not in Greece like in the movie).

As a child, Mayol spent all his summer holidays in Japan, in Kyūshū’s Karatsu area (Saga prefecture), which was easily reached using the Shanghai-Nagasaki ocean line.

It is there he first learned to skin dive with his brother, when he was 6/7 years old (1933), and recalls being fascinated by ama freedivers collecting shells in the area.

Dolphins played an important role in his life, and Jacques also saw his first dolphin near the Nanatsugama caves in Karatsu.

In inspiring a young Jacques Mayol to explore the underwater world, Japan’s traditional ama divers might have, in an indirect way, contributed to the birth of modern freediving…

Image source: www.arcgis.com