Practical

TRAVEL TIPS

-

SeasonalitySeasonality

-

Book in advance and avoid main holidaysBook in advance and avoid main holidays

-

Be on timeBe on time

-

No tippingNo tipping

-

Diver levels - metric/imperial conversionDiver levels - metric/imperial conversion

-

Getting aroundGetting around

-

Luggage-free travelLuggage-free travel

-

Driving / renting a carDriving / renting a car

-

Safety and healthSafety and health

-

Cultural note / miscellaneous infoCultural note / miscellaneous info

SEASONALITY

Japanese diving is seasonal, with a country-wide low season in the colder, to slightly colder (Okinawa) winter months.

Make sure to decide in advance which area and/or seasonal highlights you would like to focus on and plan your diving and non-diving activities around that.

And do avoid main national holidays if possible.

Waters do get cold in the north, and rental dry suits are rare, so bring your own and/or discuss this with your diving operator in advance.

Make sure to check if your sizes are available for any equipment you might need to rent, especially wetsuits and booties, and make sure you have the right thermal protection for the season – keeping in mind that temperatures can still vary a lot according to what the Kuroshio Warm current is doing, for instance.

We’re personally never warm underwater, and would rather have too much than not enough protection.

Image source: @ag.lr.88 on Instagram

BOOK IN ADVANCE AND AVOID MAJOR NATIONAL HOLIDAYS

As with many things in Japan, it is best, if not necessarily necessary to book in advance.

Especially when specific logistics are involved, such as for diving activities.

Japanese divers, like the majority of the Japanese population, have much less free-time and vacations than say European divers, for example.

This does not stop them from going diving very regularly, but also means diving activities are generally very well organized in Japan, with an effort to try to waste as little time as possible.

This also means there is usually little room for flexibility or improvisation, which is why you should always try to book in advance, rather than hoping to join a dive trip at the last minute, unless you’re in a busy diving area such as Okinawa…

Avoid major national holidays

It’s best to try to avoid weekends if at all possible, which are often very busy, as well as major national holidays, that constitute the peaks of Japanese high season for all leisure activities.

The main holidays to look out for are the Golden Week, a collection of four 4 national holidays within seven days (the core being April 29 to May 5), which, in combination with well-placed weekends, is one of Japan’s three busiest holiday seasons, besides and the O-bon week (generally August 13 to 16) and New Year’s break (which has less impact on domestic diving since it is in winter) – more on Japanese holidays here.

BE ON TIME

Japanese facilities are certainly used to dealing with visitors having only very limited time to spare, since this is the case with the majority of Japanese tourists (who as a rule work long hours and have much shorter holidays than elsewhere).

This means they are very efficient in terms of organisation (a good example of this are the tourist information desks often found in Japanese train stations, very useful in helping you organize your visit efficiently).

However, also because of this time pressure, last-minute changes are generally not appreciated.

Likewise, we recommend that you make sure to always be on time in Japan.

The Japanese often having a very tight schedule, customers showing up 30 minutes late is not only rude/inconsiderate from a cultural point of view, but can also seriously compromise the timed plans of other visitors/divers.

Don’t waste other people’s precious time!

One way to approach this is to consider that in Japan, being on time for diving means being there – and ready – 5 minutes in advance!

NO TIPPING

Importantly for people coming from a strong tipping culture, there is no tipping in Japan, at least not in a commonly encountered commercial service setting.

Some form of tipping actually does exist, but it is restricted to specific, traditionally defined contexts and is highly formalised, so of absolutely no concern to tourists and visitors.

If you want to give something, bring little gifts, especially food, snacks and drink specialties from your country or current home-base (which is what Japanese tourists usually do as well).

Japan, like other Asian countries (Thailand, for instance or Indonesian oleh-oleh, and more…) has a strong small gift-culture, called omiyage, which you do not need to partake in, but will the intention will be appreciated if you do (your gifts would fall in the temiyage category) – more on this here.

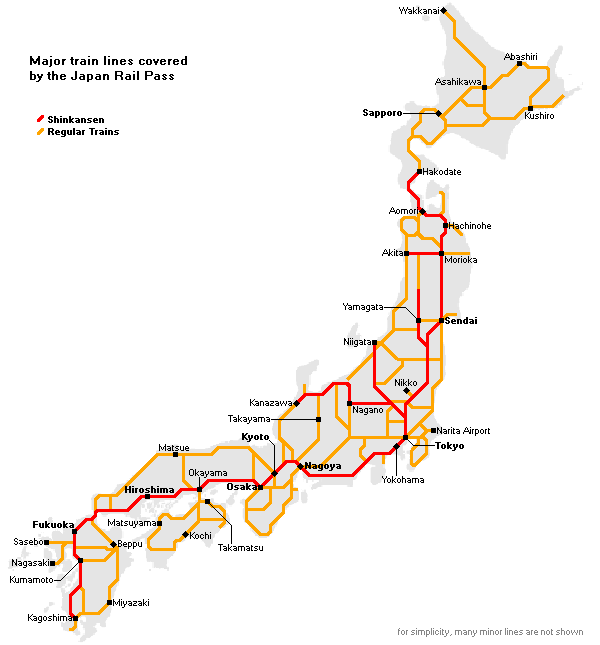

GETTING AROUND

Japan’s main international transit hubs being Tōkyō, Ōsaka and, to a certain extent, Okinawa, for arrivals from neighbouring Asian countries.

The country is particularly well-connected internationally thanks to its major international airports, and domestically through numerous regional airports, an impressive train network as well as inter-island ferries. The road networks is efficient, even though the country’s mountainous topography does limit the efficiency of road travel to a certain point.

The Pacific Belt area (see here) in particular, concentrates Japan’s biggest cities into one hyper-connected megalopolis.

Visitors coming from abroad will most likely land at Tōkyō’s Narita International Airport, whilst Tōkyō International (more commonly known as Haneda Airport) concentrates most of the domestic flights to and from Tōkyō. Ōsaka’s Kansai International Airport (Kankū ) is the country’s second-biggest hub, and has a dedicated Low Cost Carrier terminal nearby.

Okinawa Main Island and Ishigaki’s international terminals receive both domestic flights but also flights from neighbouring countries of the Asian mainland, Hong-Kong and Taiwan.

All of Japan’s larger cities are serviced by public transportation, including subways or trams, buses and also by private taxis.

And all islands of Japan usually also offer some sort of public transport services to most areas, and even to remote highlights – a large railway station’s tourist information office is your best bet to get all the info you need, and they are usually friendly and efficient.

Domestic travel on the main islands primarily means trains, especially through Japan’s highly efficient network of Shinkansen “bullet-trains” (for which non-residents can get an unlimited JR rail pass for a set period – this needs to be bought outside Japan).

There is also a solid network of domestic flight routes through the main domestic carriers and low-cost airlines, which make it easy to go from a major city to a more remote areas or island, such as the Nansei islands.

Non-residents can get discounts on domestic airfares through dedicated air passes, such as the ANA Experience Pass or the JAL Explorer Pass.

LLC / low-cost air carriers operating in Japan are also a good, although clearly not ecologically ideal, way of reducing transport costs.

For instance, reaching one of Japan’s most popular diving destinations, the Okinawa region, is relatively easy, requiring only a short flight from Tōkyō or Ōsaka to Okinawa’s Naha or Ishigaki in the Yaeyama islands. Similarly, reaching the Izu Island’s more remote Hachijō-jima is relatively easy, as it is only a 40-minute hop from Haneda airport.

However, not all of the islands offering great diving have airports, and divers may find themselves taking fast ferries (to go from the Izu Peninsula to the near by Izu islands, from Okinawa’s main island or Kagoshima to the Satsunan islands for instance).

In some case, the only way to go will be slower, overnight ferries to some of the more remote locations (Japanese ferries often have some sort of sentō, communal hot bath, which allows you to bathe while watching the ocean go by, quite relaxing …).

This includes very remote Ogasawara/Bonin islands located far south in the Philippine Sea, which can only be accessed through a 24-hour+ ferry ride from Tōkyō.

The ferry only leaves on certain days of the week, making it one of the most remote diving areas in Japan.

While this form of slow-travel certainly does have its charm, it also means more time, planning and scheduling to get to dive there.

LUGGAGE-FREE TRAVEL

Courier services (called takkyū-bin in Japanese) are very popular in Japan, highly reliable, and not super expensive AND can take care of your luggage!

This makes it very easy to send your luggage ahead of you to your destination.

Your hotel, local convenience store or local post office or even airport should be able to help you organise this.

It is quite common for domestic tourists use these to forward their main luggage and dive gear ahead to their destination, to avoid having to carry it with them.

You can also send luggage from an airport or major stations to your hotel or accommodation, for instance, which is great if planning to use public transportation after a long international flight for instance…

Do try luggage free-travel if you get the chance!

DRIVING / RENTING A CAR

It is possible to rent a car in Japan, but keep in mind that most highways are toll-roads and it quickly adds up for long distances.

Also, Japan did not ratify the 1968 Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, meaning that international permits issued by countries having ratified the 1968 Convention are not recognized in Japan (which is still under the 1949 Geneva Convention on Road Traffic).

If your international permit was issued by a 1968 Vienna Convention country, such as France for instance, you will instead need to get an official translation of your national driver’s licence to be allowed to drive in Japan.

This is a fairly straightforward and painless process, which can be done in a day at a local Japan Automotive Federation (JAF) office and costs a few thousand yen.

More on this, and on driving in Japan here.

"A foreigner is driving this car" bumper stickers found on Japanese rental cars...

SAFETY AND HEALTH

Japan is a very safe country, compared to most other destinations, and one where you won’t generally have to worry about crime or theft. More on this here.

While you can and should trust your diving operators, as everywhere else in the world, people might prey on tourists in places where they gather, so keep an eye out for your belongings.

The main dangers you might face in Japan are natural ones (see here), linked to the power of the elements…

Yet even when disaster strikes, things are usually quite well organised in Japan, which features some of the best disaster handling infrastructures in the world…

When it comes to diving and insurance, this is also in no way specific to diving in Japan, but we strongly advise you to get specific insurance coverage for dive trips, covering planned diving activities and emergencies, including medical evacuation and hyperbaric treatments such as DAN, DiveAssure, Diveassist or eventually a more general insurance policy that clearly covers recreational diving activities, such as those offered by WorldNomads, SafetyWings or others.

Some insurance companies like Dive Assure offer packages covering the duration of a single trip.

If you are already covered by general travel insurance, make sure to check that it does indeed cover your planning diving activities in Japan or elsewhere, and other key aspects such as hyperbaric recompression treatments and medical evacuation / repatriation from Japan.

In case of post-dive problems, Dan Japan has a 24/7 Japanese emergency hotline

+81-3-3812-4999, with an English-speaking operator available Monday to Friday between 9am and 5pm at +81-45-228-3066 – the operator / medical team can give you advice if you’re worried about something after a dive, whether you are a DAN member or not (but only member’s medical expenses are covered)

There are recompression chambers in most major cities and diving areas in Japan, but these can be relatively far from the dive sites, so it’s best to dive conservatively, within the guidelines given by your computer, to maintain slow ascent rates of 10m per minute max, and to remember to stay well hydrated before and after the dive.

As a friendly reminder, even though hot-springs are often found next to dive sites (at the Izu Ocean Park, for instance) and as incredibly tempting as it might seem, hopping into the warm waters a hot-spring/onsen straight after a dive is not recommended as it affects blood circulation, which could affect bubble formation could possibly interfere with off-gassing, not unlike hard-drinking after diving…

Like sports after diving, jiko-sekinin (self-responsability) or not, it is recommended to wait a few hours before indulging…

CULTURAL NOTE

Cultural note: Do think of others, and keep your cool!

As a general rule, in all your actions and interactions in Japan, try to be considerate of others, and try avoid causing inconvenience (meiwaku 迷惑 in Japanese), which is vast and complex subject, linked to context, and can include behaviour not frowned upon elsewhere, such as speaking loudly…

Best way to do so is to look around and observe how people are behaving/interacting around you, which usually helps a lot.

Should a problem arise, however, be sure to keep your cool.

As elsewhere in Asia (which Japan is a part of though it’s easier to forget than elsewhere), getting angry and shouting is seen as immature, and is never a good way to try to resolve issues – not only will not help you much, but it raising your voice might actually play against you.

It is not always easy to do so, especially when you can’t get your point across clearly because of language issues, but make sure to keep your cool, and to focus on the issue at hand and what can be done practically.

And keeping a (personal) sense of humour usually comes in handy.

MISCELLANEOUS INFO

Languages – Japanese (many Japanese are able to understand English to a certain extent, since it is taught in school as part of compulsory education.

You can also refer to our phrasebook and diving vocabulary here

Currency – JPY (Japanese Yen) – see current exchange rate here (no tipping necessary)

Timezone – UTC+09:00

Dial Code – +81

Electricity – 100 V / 50 Hz / 60

Power Plug Type – A, B

Japan’s nationwide emergency phone numbers are:

| Police: | 110 |

| Ambulance/Fire: | 119 |

Internet offers in Japan are way more expensive, and people usually pay more than 50 euros a month for some sort of optic fiber plan (usually with a 2 year contract and installation fees), excluding phone offers, and there is usually some sort of data cap hidden somewhere…

Most Japanese people are not aware of this situation, because of limited access to information not in Japanese, and the usual national monopolies keeping prices high.

Service itself, internet speed and reliability for example, is also not on-par with what you would find elsewhere in Asia, especially for the prices paid, and quite a let-down for a country with such modern infrastructure and a technologically advanced image.

What this means is that internet offers for tourists and visiting travellers, usually bought/rented on arrival at the airport, will be expensive, and not as great as one would expect, especially in rural or more isolated areas…

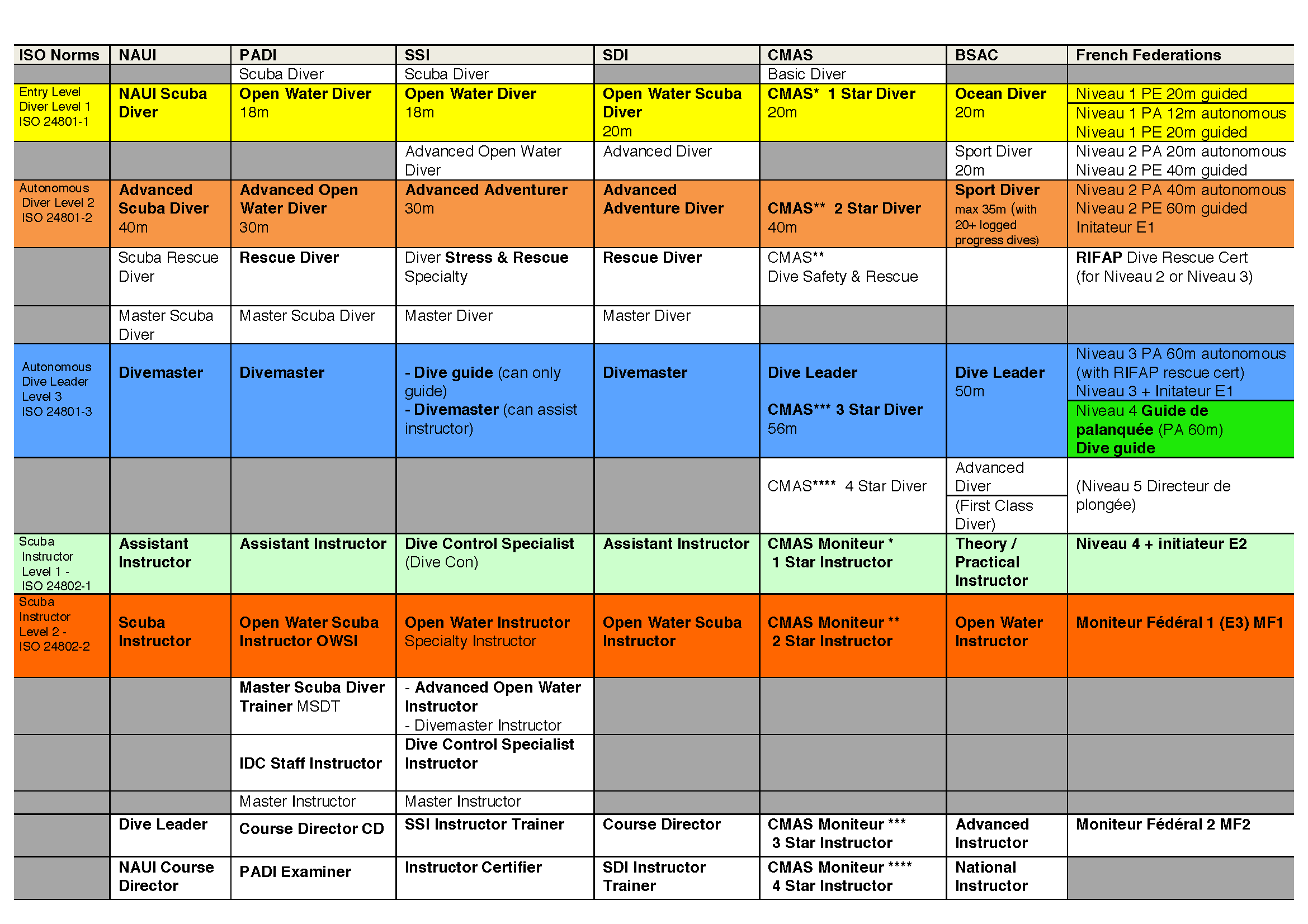

CMAS / RSTC DIVER LEVELS METRIC / IMPERIAL CONVERSION

Diving certification cheat-sheet

The majority of Japanese dive centres will be (W) RSTC-affiliated (PADI, NAUI, SSI, SDI…)

If you are a CMAS-certified diver, and only have a CMAS certification, we strongly advise you to make sure to bring you certification card with you, as it can be difficult to justify your training level without it, since there is no real cross-federation centralised diver database accessible online.

Most dive centre professionals will have no problem understanding your certification level, and the following (rough) equivalence is usually applied:

CMAS * diver > Open Water diver

CMAS ** diver > Advanced Open Water diver

CMAS *** diver / CMAS **** > Rescue or Divemaster

Instructor, supervisor, moniteur > OWSI Instructor

Obviously, this somewhat reductive, as the real training situation is much more complex, with very real differences between RSTC and CMAS standards and requirements for different levels, but does follow current ISO norms.

Metric / imperial cheat-sheet

RSTC standards are only given for training dives within a agency’s curriculum.

As such, RSTC agencies do not specify any actual depth standards for recreational, “fun diving” done outside of a training context, and simply recommend divers to stay “within the limits of their training and experience”, and not to dive deeper than 40m.

That said, one should keep in mind that, should an accident occur, the dive centre and dive professionals involved will have to be able to justify their decisions and actions, under the angle of duty of care

Which is why, in practice, most RSTC-affiliated dive centres will usually apply the following maximum depths, given for training dives in their agency standards, to actual exploration / “fun” dives:

– 18m max for an Open Water diver,

– 30m max for an Advanced Open Water diver or more, and

– access to the 30 to 40m depth range given at the discretion of the dive centre/guide and the diver, depending on their experience, comfort level and/or training.

We hope this clears up the situation, and helps to understand why we all should respect a dive centre and/or dive professional’s guidelines, even if they are seem overly conservative, and always respect all indications given in the dive briefing as well as local rules and regulations.